By Monique Jones

The Birmingham Times

When you step on the 95-year-old wooden floors of the auditorium and grand ballroom on the second and third floors of Birmingham’s historic downtown Masonic Temple building, you can’t hear a squeak.

The ballroom, which seats up to 2,000, is where legendary acts—Dizzy Gillespie, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Birmingham native Erskine Hawkins, and many others—performed at the start of their celebrated careers.

The Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge, Free and Accepted Masons (F & AM) of Alabama, Temple Building, a seven-story structure on the corner of 17th Street North and 4th Avenue, is an architectural marvel. Besides the well-preserved floors, its ballroom features elegant décor, such as Renaissance Revival–style columns with ornate capitals.

Over the years, the landmark building in the 4th Avenue Historic District has hosted its share of notable musicians and housed the offices of several black doctors, dentists, lawyers, and other professionals, as well as the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). Today, it is undergoing a reconstruction project to preserve the building’s rich history.

“Too much history is invested into this building that assisted too many people of color not only of Birmingham but also of the state of Alabama,” said William Dean Anderson, Right Worshipful (RW) Grand Junior Deacon and Operations Manager.

The renovation aims to preserve both the history and the structure.

“We need to preserve this [building] so future generations will understand the struggles that took place for the right to vote, for the right to just assemble,” he said.

The Masons moved out of the building about seven years to an adjacent building to save on the costs of keeping up the facility.

Cornerstone of the Community

The Masonic Temple served as headquarters for leaders and protesters during the civil rights movement, said Joseph C. Clark III, CEO of Community Concepts Agency Inc., the company hired to oversee the project.

“… The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., [Birmingham lawyer] Arthur Shores, and the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth met in that building basically because it was bombproof,” said Clark. “Shores started the desegregation of schools, his first lawsuit, because he had an office in the building. [The lawsuit] was filed from there.”

Several medical professionals with offices in the Masonic Temple helped people who couldn’t get help anywhere else, particularly those leading [civil rights protests] and [getting] wounded in the streets. Doctors and surgeons in the building regularly tended to protesters who had been bitten by police dogs, Clark said.

The building also played a key role in the everyday lives of many residents, including Birmingham Mayor William Bell.

“At the age of 13, I attended my first formal dance on the second floor of the ballroom,” said Bell, who pointed out that he also went to the building for his regular dentist appointments.

“I used to take piano lessons on the fourth floor, too,” he recalled. “It was a place where, every Saturday, I found myself being attracted to [and] really immersed in black society.”

“The Masonic Temple, for as long as I can remember, even as a child, was the center of the [city’s] African-American business community, African-American culture, African-American society in general,” Bell said. “That building also represented a coming together of the entire community because a variety of professional services, such as black doctors, insurance companies, and lawyers were located there. [The Masonic Temple] has a lot of fond memories for me [and for] a lot of people who understood the value of the diversity that the building represented in its heyday.”

Place of Gathering

Birmingham’s historic Masonic Temple, built by the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge, F&AM of Alabama, began construction in 1922 and was opened in 1924. It became the central hub for Alabama’s Prince Hall Masons and grew to become much more.

“It provided a place of gathering. There were no restrictions. People of color could come in through the front door, and there would be no mandates placed on them. They could operate freely,” said Anderson. “Whenever other venues were not large enough, such as the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church or the A.G. Gaston Motel, [civil rights] strategy meetings were conducted here to accommodate the size of the audience. Voter registration efforts took place in the building, as well.”

The Booker T. Washington Library, now the Smithfield Library, existed in the Masonic Temple for about 30 years before moving.

“… I’ve come to realize that this building always has been more than just a place where masons come to meet,” said lodge Grand Master Corey D. Hawkins Sr. “It was actually a hub for the 4th Avenue District, a place where African-Americans could go and not have to worry about being forced to enter through the back door or sit in the balcony. If they sat there, it was by choice.”

Birmingham’s 4th Avenue Historic District stretches along three blocks of 4th Avenue North, from 15th to 18th Street, and is notable as a center for businesses that served blacks during the city’s long period of enforced segregation.

Clark said the Masonic Temple “represents the strength and faith that the lodge had in the city and [the ability to] support services for folks who couldn’t afford [them] or were turned away from white establishments. This was especially important during the Jim Crow times.”

The building also can be traced to the heyday of musical icons, said Clark, noting performances by Gillespie, Ellington, Erskine Hawkins, and others: “If you look back in [the musicians’] histories, this was a place to come. This [building] has deep ties to the music profession. It’s something the lodge would like to see carried forward with the legacy. … If we can continue this, … what the building has done and what the building continues to do lives on.”

Marvel of Architecture

The Masonic Temple building was meant to last, as evidenced by the condition of the 95-year-old wooden floors in the auditorium.

“They don’t build them like this anymore,” said Clark. “We’d like to [not only] restore its beauty … [but also] continue its story.”

Clark, a retired licensed general contractor and business consultant, said he was “honored” to be chosen for the revitalization project.

“I have 45 years of experience as a licensed general contractor, and I’ve done several of these types of projects. You just have to marvel at the craftsmanship of each and every one of these columns, the woodwork, the marble walls,” he said, describing the auditorium.

Coupled with the room’s Renaissance Revival–style décor, it’s easy to see how impressive the building was in its heyday.

“If you look at the columns, the decorative aspects of the wall sconces and appliqués, that’s what we want to preserve, along with the story of what this building did for the black community in the early-1900s in Birmingham,” Clark said.

Artifacts of Times Past

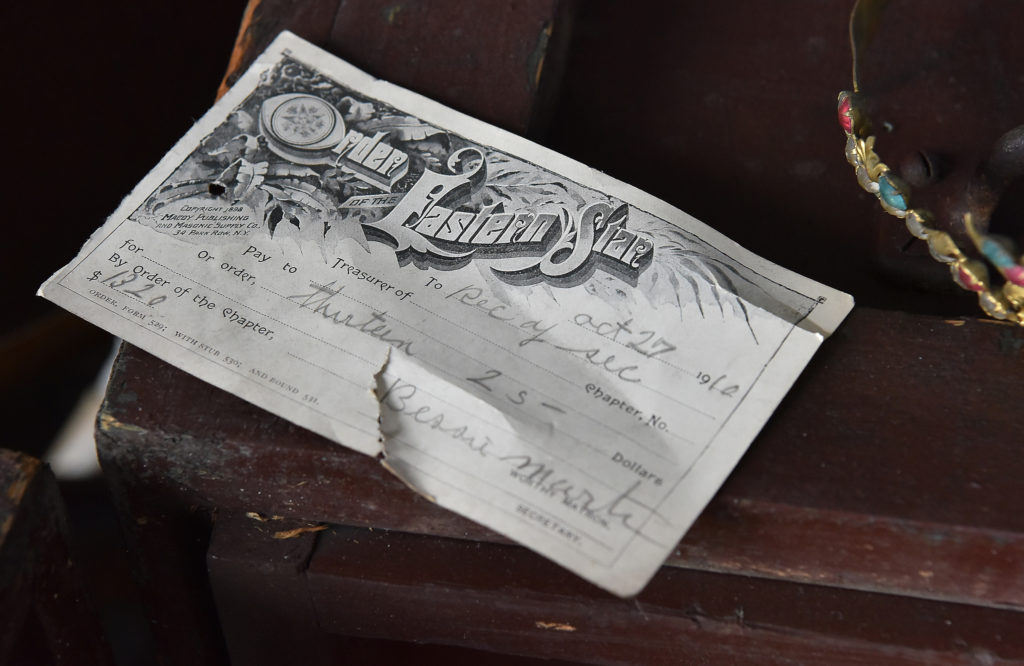

Remnants of times past are scattered throughout the Masonic Temple.

On one of the building’s upper floors, a dentist’s office still houses vintage equipment and a former recording studio still has pictures of musical groups taped to a door. In the basement, one can find dental equipment from the late-1800s and early-1900s, as well as office supplies and equipment from that time, such as wrought-iron typewriters.

The basement also had been outfitted as a bomb shelter. Civil-defense supplies from the 1950s and 1960s, including water and canned biscuits, are reminders of Birmingham’s Jim Crow past. The lodge members and Clark plan to use these artifacts as museum pieces once the building is reopened.

“When you tear down a building, a lot of people just see it as a physical act. But when you destroy the physical building, you take with it its stories, its history, its impact on the community,” said Clark. “[The Masonic Temple] is a beacon for the black community to take pride in. … [The renovation effort will ensure that] the continuity carries through for the black community … [and the building] will be a center of pride once again for another 100-something years.”

Historic Tax Credits

Mayor Bell said the city will help restore the Masonic Temple’s former polish.

“We’ve been looking at ways to use historic tax credits and other financial tools to assist the masons in rehabilitating that building,” said Bell. “…That building will be the anchor for the western part of downtown Birmingham. If we can stimulate economic growth and bring more people to that location, it will help spur prosperity for smaller businesses that are already located in the area and attract other businesses, as well.”

Alabama’s Prince Hall Masons have started a GoFundMe page to raise $500,000 for the first phase, which “will cover the planning, assessment work (environmentally-safe removal of potentially hazardous materials), and further the redevelopment concepts” for the building. Other funding is expected to come from the National Park Service.

Donations for the Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge, F & AM, Temple Building revitalization project can also be sent to the Prince Hall Legacy Foundation Inc.: 319 17th St. N., Suite 220, Birmingham, AL, 35203.

African American Registry and Black Past contributed to this post.

Some Well-Known Prince Hall MasonsRobert Sengstacke Abbott, founder and publisher of the Chicago Defender newspaper Richard Allen, founder and first bishop of the African Methodist Episcopalian (AME) Church William “Count” Basie, orchestra leader and composer James Herbert “Eubie” Blake, composer and pianist Thomas Bradley, 38th mayor of Los Angeles, Calif., 1973–1993 Nathaniel “Nat King” Cole, jazz entertainer and television host William Edward Burghardt “W.E.B.” DuBois, educator, author, historian, and civil rights activist Edward Kennedy “Duke” Ellington, orchestra leader and composer Medgar Wiley Evers, civil rights leader James Forten, abolitionist and manufacturer Timothy Thomas Fortune, journalist Alex Haley, author William C. “W.C.” Handy, composer Augustus Freeman “Gus” Hawkins, U.S. Congressman for California’s 29th District, 1975–1991 Lionel Hampton, orchestra leader and composer Matthew Henson, explorer Benjamin L. Hooks, National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) executive director, 1977–1992 Daniel “Chappie” James, U.S. Air Force general John H. Johnson, publisher of EBONY and Jet magazines Thurgood Marshall, U.S. Supreme Court associate justice, 1967–1991 Benjamin Mays, 6th president of Morehouse College, 1940–1967 Ralph H. Metcalfe, Olympic track and field champion; U.S. Congressman for Illinois’s 1st District, 1971–1978 Scottie Pippen, forward for the National Basketball Association’s (NBA’s) Chicago Bulls Asa Phillip Randolph, civil rights and labor movement leader Charles B. Rangel, U.S. Congressman for New York’s 13th, 15th, 16th, 18th, and 19th districts, 1971–2017 Sugar Ray Robinson, welterweight and middleweight boxing champion Arturo Alfonso “Arthur” Schomburg, historian, writer, and activist Carl B. Stokes, 51st mayor of Cleveland, Ohio, 1968–1971 Louis Stokes, U.S. Congressman for Ohio’s 11th District, 1993–1999 Booker T. Washington, educator, orator, and founder the Tuskegee Normal School for Colored Teachers (now Tuskegee University) Egbert Austin “Bert” Williams, Vaudeville entertainer Harry A. Williamson, author and Masonic historian Andrew Young, U.S. Congressman for Georgia’s 5th District, 1973–1977; U.S. Ambassador the United Nations, 1977–1979; mayor of Atlanta, Ga., 1982–1990

|

Other stories in this series:

Restoring The Most Worshipful Prince Hall Grand Lodge Building to its grandeur

Alabama’s Prince Hall Masons have rich history in self-improvement, social responsibility