By Ariel Worthy

The Birmingham Times

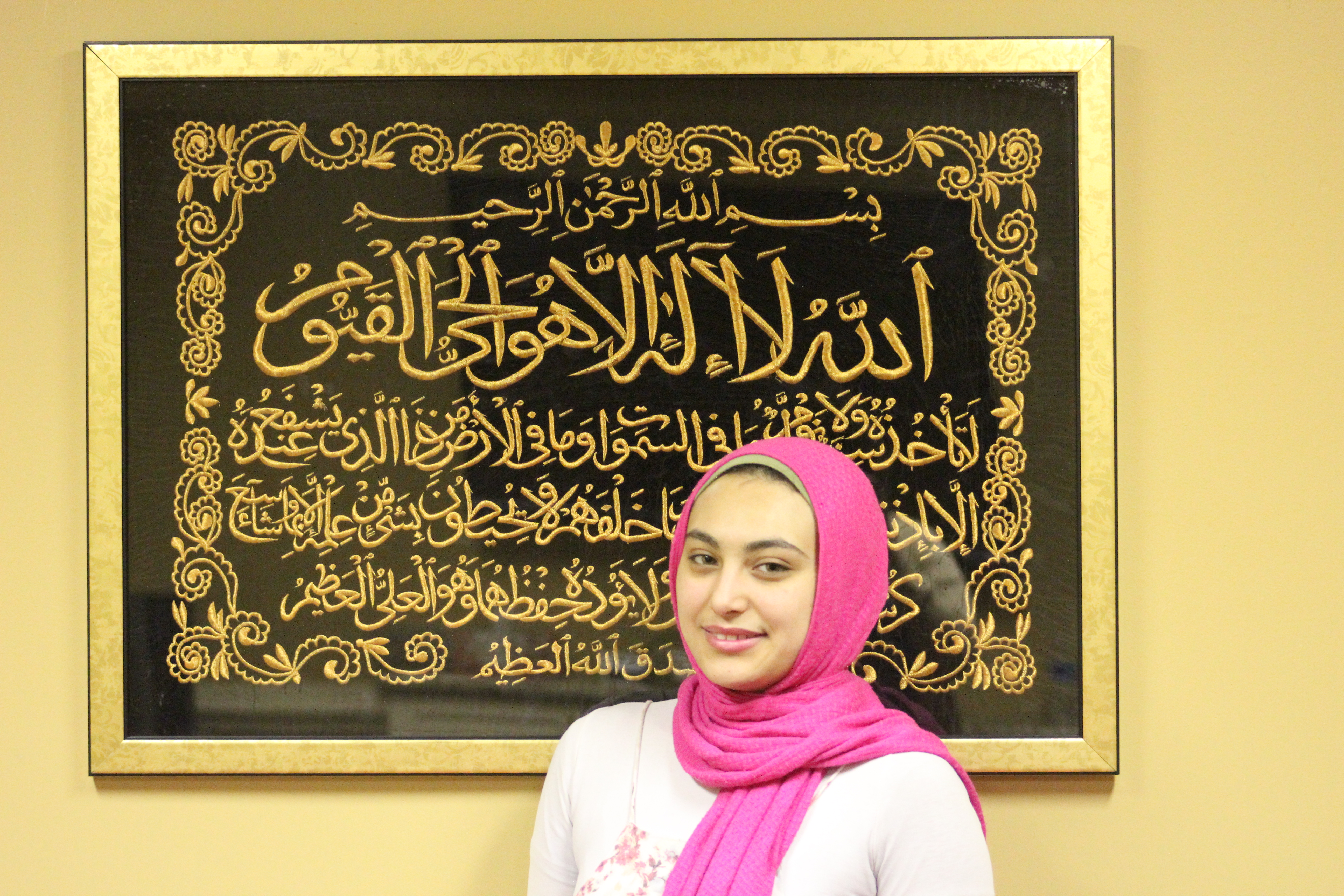

Rowan El-Qishawi, an 18-year-old freshman at the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) who has already been acknowledged nationally for her scientific work, said she wants to help dispel several misconceptions about Islam.

“I want people to understand that Muslim women are not oppressed,” she said. “We have access to education. We’re not in arranged marriages. Here I am, 18 years old, doing an international science project. I don’t see what’s so oppressing about that. Just because I wear this scarf doesn’t mean I’m any more oppressed than anyone else. I wear this scarf as my way to submit to God, and that’s beautiful to me.”

While at Hoover High School, El-Qishawi attended the Intel International Science and Engineering Fair (ISEF), the world’s largest pre-college science fair. At the event, held in Phoenix, Ariz., 72 countries were represented and 2,000 students presented projects.

“These are your top-notch students,” El-Qishawi said. “A girl made a cane to assist deaf people and a hand to help blind and deaf people. I was so humbled by it because out of all of the people I got chosen.”

El-Qishawi’s project was impressive, as well. She introduced an antibiotic that could cure Huanglongbing (HLB) disease, a citrus-greening disease that affects citrus plants all over the world. The disease has cost the citrus industry about $3 billion, and billions are being paid to some universities in California to find a cure.

“It potentially can be used in hand sanitizers, also,” she explained. “It broke down E. coli when I was researching it, but I will have to do a bit more research before I can be sure.”

El-Qishawi, who has done research in several areas over the past five years, said she’s not looking for a big payout.

“I don’t do these things because I want to be recognized. I genuinely want to help,” she said. “If my research can help cure a disease, why not do it?”

In her research for the antibiotic, El-Qishawi uses ladybug blood from an Asian species: “These are not your normal American ladybugs. These are an Asian species. They’re a lot bigger. When they feel scared or see a predator, they start to bleed from their knees. This yellow hemolymph has a distinct smell that is supposed to drive away predators, kind of like a skunk’s spray. I broke down the blood and saw that there could be a potential cure for [HLB] disease. Because it has a distinct smell, it could be used as a pesticide. This would be an organic pesticide, but I’m not sure. I’ve been so busy with college that I haven’t been able to look into it.”

El-Qishawi also is passionate about the environment. “Protect the place where you live,” she said. “God gave it to you. Give it back in a good condition.”

Some have made insulting comments when they learned she was a Muslim and a scientist.

“I’ve heard things like, ‘You study science, so you make bombs,’” she said. “That’s so ignorant … it’s an eye-opening experience.”

That’s why her work is so important.

“Besides helping people, it’s also helping people understand and have a different perception about Muslims. A lot of times, people have never met a Muslim before, and all it takes is meeting one.”

El-Qishawi said she believes in empowering women.

“One of the things I do with all the science and research is show people that Muslims are your scientists, your engineers,” she said. “If an 18-year-old Muslim girl can go and make her own antibiotic and pesticide on an international level, then you dare not say I’m oppressed, you dare not say I’m a terrorist.”

El-Qishawi said she wants to teach people to not focus on her scarf but rather on what she does as a person. That can be difficult, however.

“When I was 14 years old, I was at the library, and just as I walked in a kid walked out of the elevator and said, ‘Look, daddy. There’s one of those terrorists you were talking about.’ He said it with absolute fear. I went to my mom’s car and cried. As soon as I got to the car, I took the scarf off.”

But El-Qishawi eventually put it back on because she knew she had to wear it.

“I wear this scarf as a walking ambassador for Muslims,” she said. “I want you to come to me and ask me questions. I want you to learn.”

El-Qishawi, who eventually hopes to become a doctor, said she wants to demonstrate the importance of diversity.

“You need people who are more culturally integrated into society,” she said. “It’s sad that people say if you’re not pretty you’re not good enough. You may not see all of me in my scarf, but I am beautiful, and I am good enough.”