By Solomon Crenshaw Jr.

For The Birmingham Times

For Natasha Rogers, executive director of the Negro Southern League Museum (NSLM) in downtown Birmingham, the museum and its central city location are a “match made in heaven”—and she would know.

The combination of Railroad Park, the NSLM, and Regions Field in the Parkside District has led to billions in private investments for the area and attracted hundreds of thousands of visitors from around the globe. And Rogers was the special events coordinator at Railroad Park before crossing First Ave. South to lead the museum.

“Railroad Park was literally the catalyst for all the economic development you see,” Rogers said. “Soon after Railroad Park came Regions Field, and here we are. We are very excited about the energy. I think it’s nice for the residents to have something to do and to see the momentum that’s coming to Birmingham.”

Railroad Park, Regions Field, and the NSLM opened in 2010, 2013, and 2015, respectively. And all three have worked in tandem.

Birmingham Barons General Manager Jonathan Nelson can vividly remember the final days of construction of Regions Field as the minor league baseball team made its return to the Magic City from Hoover in 2013.

“We’ve been a natural fit to celebrate the legendary men and women who were part of the Negro League for so long and were so important to this community,” Nelson said. “It goes hand in hand with a perfect baseball day: being able to go over there and see the history of Negro Southern League Baseball in this community and, of course, go to a Barons game, as well—it’s a perfect fit.”

The Barons begin the 2017 season on the road, Thursday, April 6, at the Jackson Generals. And the team’s home opener is Wednesday, April 12, when the Barons host the Montgomery Biscuits.

A Downtown Destination

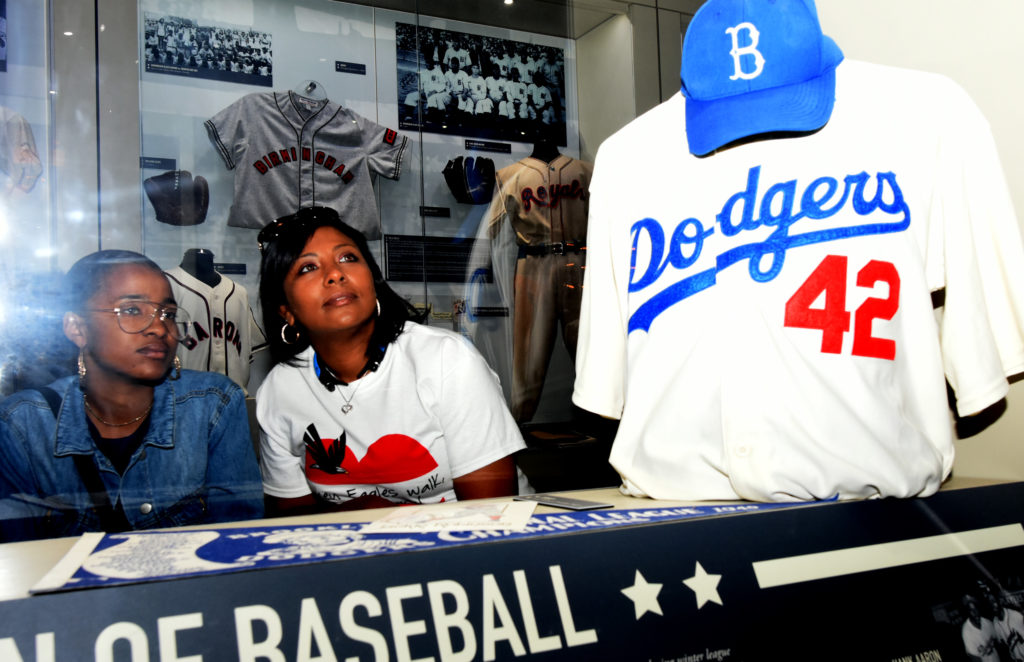

The NSLM has become one of downtown Birmingham’s key destinations. Since its opening in 2015, nearly 20,000 people have visited the museum, which explores the integration of baseball and highlights players from Birmingham who made it to the major leagues.

The facility has 8,000 square feet of exhibit space, as well as a full-time research center, making it the largest African-American sports museum with baseball artifacts from the Negro leagues in the country.

Renowned Negro League baseball historian and researcher Dr. Layton Revel, who lent his collection of artifacts for display, says it’s even larger than the Smithsonian Institution’s museum on African-American sports.

The NSLM also highlights the Birmingham Industrial League, as well as modern players like Bo Jackson, Frank Thomas, Ron “Papa Jack” Jackson, and Michael Jordan, all of whom famously played for the Barons.

Legends

Birmingham is home to more living Negro League legends than any other city, according to the museum.

“People get a kick out of meeting them, hearing stories, getting autographs,” Rogers said. “And the players enjoy sharing a part of their lives that they were passionate about.”

Mayor William Bell, who attended the funeral of Negro Leaguer Cleophus Brown Sr. on Saturday, March 18, said the museum provides a way to preserve the memory of not only of Brown but all Negro League players, including those who were part of the Birmingham Black Barons.

“[The NSLM’s] attendance is growing every year,” Bell said. “As people go to the museum to learn the history of baseball in this community, the word gets out. It’s drawing more and more attendance while preserving the legacy of those who played in the Negro League.”

Formed in 1920 by a group of African-American businessmen, 27 years before Jackie Robinson broke the Major League Baseball race barrier, the Negro Southern League served as a feeder league to the Negro American League and the Negro National League, according to the city of Birmingham.

Artifacts

Among the NSLM’s collections are a display of Jackie Robinson breaking the baseball color line (celebrate Jackie Robinson Day at the museum on April 15); the game-worn uniform of pitching phenom Satchel Paige; and a holographic display of Woodlawn High alumnus and current University of Alabama at Birmingham student John Cross portraying Paige.

The Wall of Balls, a favorite of former players and their families, honors those who have passed away. Each baseball, 1,500 in total, is signed by an individual player, and the players and their family members enjoy pointing out the signed mementos when they visit.

Rogers said a plantation bat on display tugs at her heart.

“That’s my favorite,” the executive director said. “When you think about the slaves and what they went through, and how a slave took the time to carve a bat so he could have a little relief, that’s just powerful to me.”

Rogers is part of the Negro League family in more ways than one. She said she’s been adopted by players who have visited to sign autographs and tell stories of days gone by, and she also is a descendant of a player: her great grandfather, Clarence Orme, was a Negro Leaguer in Kansas City, Mo., playing for the Kansas City Giants and Kansas City Monarchs.

“I never met him, but when I learned that he played, it increased my sense of pride and purpose,” Rogers said. “It also increased my drive to want to make the museum successful and further the museum’s mission to educate the world about the Negro League and the impact Birmingham had on the sport of baseball.”

Birmingham Story Line

The NSLM’s artifacts are on loan from Dr. Layton Revel, who has dedicated himself to preserving the legacy of Negro League baseball. The Birmingham museum stands apart from the Negro Leagues Baseball Museum in Kansas City, Revel said.

“Our story line tells the history of black baseball in America through the eyes of Birmingham,” he told Alabama NewsCenter in July 2015. “We’re looking at the national pastime from the perspective of one local area. The focus is significantly different, but the history is so rich in black baseball that one museum cannot tell the whole story.”

Revel has said that Birmingham is an ideal site for such a museum. The Birmingham Black Barons—a charter member franchise of the Negro Southern League that began in 1920 and lasted through 1962, when the league folded—was one of the longest running Negro League teams. And the legendary Rickwood Field, still the nation’s oldest active ballpark, served as home field for not only the Black Barons but also the Birmingham Barons (prior to their move to the Hoover Metropolitan Stadium).

Next Phase

The next phase of the NSLM’s development is an online souvenir shop and an onsite restaurant with a rooftop view of Regions Field.

“Hold on to your socks because another announcement is coming,” Rogers said. “We’re taking our time to make sure that people will be pleased when the museum finally does put out these new things. We’re not only looking for a good partner for the museum but also a good entity that will attract [more] people to the area.”

The Negro Southern League Museum

Website: www.birminghamnslm.org

Address: 120 16th St. S, Birmingham, AL 35233

Telephone: 205-581-3040

Admission: Free

Hours of Operation: Monday, 11 a.m.–5 p.m.; Tuesday, 8 a.m.–5 p.m. (Tour Tuesday); Wednesday through Friday, 11 a.m.–5 p.m.; Saturday: Noon–5 p.m.; Sunday, Closed.