By Hillel Italie

AP National Writer

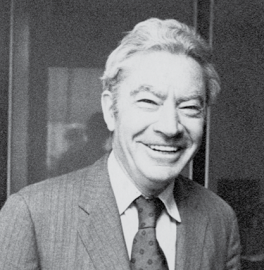

NEW YORK (AP) – George Braziller, an independent and self-taught publisher for more than 50 years who supported early novels by Norman Mailer and Arthur Miller and released fiction by Nobel laureates Orhan Pamuk and Claude Simon, has died. He was 101.

A spokesman for his publishing house, George Braziller Inc., told The Associated Press that Braziller died Thursday at the Mary Manning Walsh Home in Manhattan after a brief illness. Braziller had stepped down as publisher at age 95 and turned over the company to his son, Michael Braziller.

A high school dropout endowed with lifelong curiosity, George Braziller was often likened to his good friend and fellow maverick, Barney Rosset. Both were political leftists and champions of books from overseas and both succeeded by breaking rules, although Braziller was never in Rosset’s class as a troublemaker. While Rosset went to court to fight censorship of “Tropic of Cancer” and other works, Braziller concentrated on finding quality literature.

“Take lots and lots of gambles,” an industry veteran once advised Braziller, “but small ones.”

He had been running two book clubs when he decided to become a publisher and, with his wife, Marsha, founded George Braziller Inc. in 1955. His first success was a translation of a memoir about the French conflict with Algeria, Henri Alleg’s “La Question,” for which Jean-Paul Sartre wrote an introduction. Over the next half-century, he acquired works from all over the world, from Turkey’s Pamuk to Irish author-director Neil Jordan to New Zealand’s Janet Frame, whose memoir “An Angel at My Table” helped inspire a film of the same name by Jane Campion.

“I was doubly fortunate in the early years to have no preconception about my role as a publisher,” Braziller told author Al Silverman for “The Times of Their Lives,” a publishing history released in 2008. “I simply felt I was on the quest to know more about the world and how others interpreted it, and every new discovery opened to others.

Braziller published one of the first major books on Vietnam, Dr. Ronald Glasser’s “365 Days.” And through an American expatriate living in Paris, Maria Jolas, Braziller was well connected to the French literary scene. He released translations of many of the country’s most prominent writers, including Sartre, Simon, Marguerite Duras and Nathalie Sarraute, who became one of his best friends.

In the 1960s, he began acquiring art books and enjoyed critical and commercial approval with “The Hours of Catherine of Cleves,” an illuminated manuscript from the 15th century, and “Jazz,” a series of paper cutouts by an ailing Henri Matisse that had long been unavailable in the U.S. Others he published from the art world included painter Will Barnet and critic-historian Meyer Schapiro.

Braziller also had a fair track record with American literature. For his Book Find Club, which he started in the early 1940s, he selected Mailer’s sensational and profane debut novel, “The Naked and the Dead.” Braziller became close with Miller after choosing his first book, the novel “Focus.” He picked numerous works by and about African-Americans and during the height of the Cold War chose a collection of essays critical of the anti-Communist Sen. Joseph McCarthy. Peak membership of the club reached 100,000.

Born in Brooklyn in 1916, Braziller was the son of Russian immigrants and never knew his father, who died while his mother was pregnant with him. Braziller grew up poor and left school after the 10th grade, making him the rare literary publisher without a college education. Braziller enlisted in the Army in 1943 and was stationed in Europe during World War II. He returned home in 1946 and resumed work with his Book Find Club, which his wife had been running in his absence. (Marsha Braziller died in 1970. They had two sons.)

“What got me into publishing was actually my first job. I was a shipping clerk making $15 a week,” he told The Brooklyn Rail in 2005. “I got a sense of the kind of books that people were reading. And I also was influenced by the legendary English publisher Victor Gollancz, who started the Left Book Club. There was no such thing in America, so I decided to give it a chance.

“But I didn’t want to call it Left Book Club; instead I called it the Book Find Club. In other words, it was an attempt to look for good literature and distribute it.”