Special to The Times

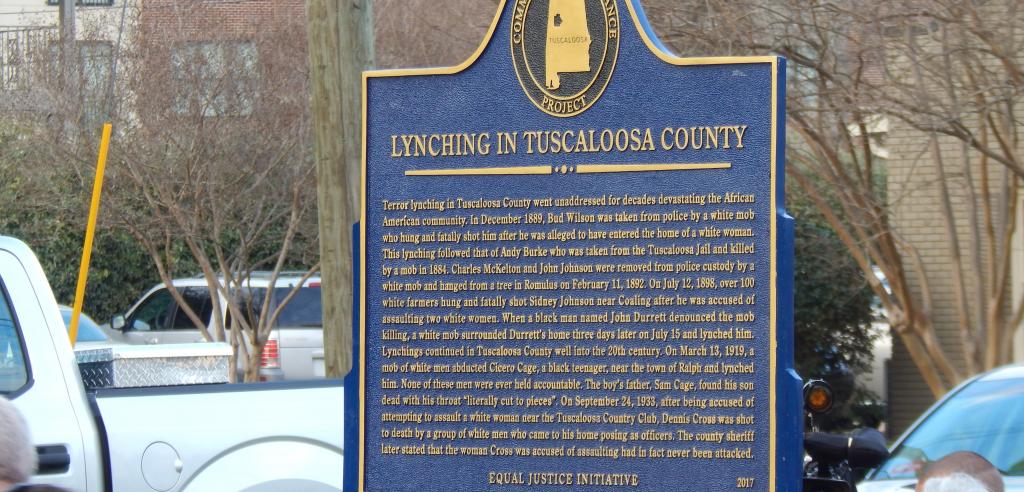

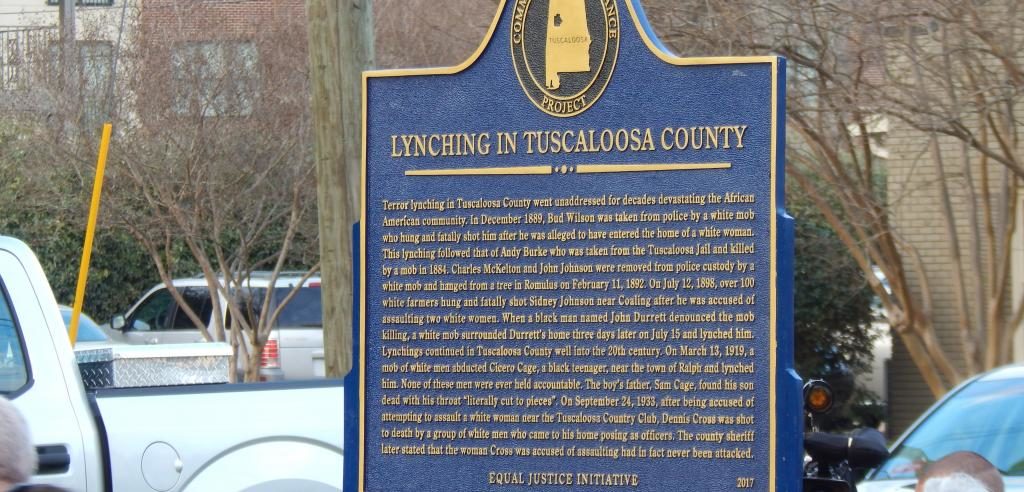

The Equal Justice Initiative this week unveiled a historical marker memorializing eight African American men lynched in Tuscaloosa County, Alabama, between 1884 and 1933. Local residents joined EJI staff in unveiling the marker at 2803 6th Street, in front of the Old Tuscaloosa Jail.

EJI erects historical markers at lynching sites as part of its Community Remembrance Project, a campaign to recognize the victims of lynching that includes collecting soil from lynching sites and creating a memorial that acknowledges the horrors of racial injustice in America.

Terror lynching in Tuscaloosa County went unaddressed for decades, devastating the African American community. In December 1889, Bud Wilson was taken from police by a white mob that hung and fatally shot him after he was alleged to have entered the home of a white woman. This lynching followed that of Andy Burke, who was taken from the Tuscaloosa Jail and killed by a mob in 1884.

Charles McKelton and John Johnson were removed from police custody by a white mob and hanged from a tree in Romulus on February 11, 1892. On July 12, 1898, over 100 white farmers hung and fatally shot Sidney Johnson near Coaling after he was accused of assaulting two white women. When a black man named John Durrett denounced the mob killing, a white mob surrounded Mr. Durrett’s home three days later on July 15 and lynched him.

Lynchings continued in Tuscaloosa County well into the 20th century. On March 13, 1919, a mob of white men abducted Cicero Cage, a black teenager, near the town of Ralph and lynched him. None of the men who lynched Cicero Cage were ever held accountable. The boy’s father, Sam Cage, found his son dead with his throat “literally cut to pieces.”

On September 24, 1933, after being accused of attempting to assault a white woman near the Tuscaloosa Country Club, Dennis Cross was shot to death by a group of white men who came to his home posing as police officers. The county sheriff later stated that the woman whom Mr. Cross was accused of assaulting had, in fact, never been attacked at all.

Following the unveiling, a dedication program at the First African Baptist Church featured remarks from local community members and from a descendant of a lynching victim, performances by Tuscaloosa area choirs, and reflections from EJI director Bryan Stevenson.

Thousands of black people were the victims of lynching and racial violence in the United States between 1877 and 1950. The lynching of African Americans during this era was a form of racial terrorism intended to intimidate black people and enforce racial hierarchy and segregation.

Lynching was most prevalent in the South. After the Civil War, violent resistance to equal rights for African Americans and an ideology of white supremacy led to violent abuse of racial minorities and decades of political, social, and economic exploitation.

Lynching became the most public and notorious form of terror and subordination. White mobs were usually permitted to engage in racial terror and brutal violence with impunity. Many black people were pulled out of jails or given over to mobs by law enforcement officials who were legally required to protect them. Terror lynchings often included burning and mutilation, sometimes in front of crowds numbering in the thousands.

In response to this racial terror and violence, millions of black people fled the South and could never return, which deepened the anguish and pain of lynching. Many of the names of lynching victims were not recorded and will never be known, but EJI has documented more than 350 lynchings in Alabama alone.

EJI believes that by reckoning with the truth of the racial violence that has shaped our communities, community members can begin a necessary conversation that advances healing and reconciliation.