By Donna Cope

Alabama NewsCenter

Renowned attorney Bryan Stevenson sees Tuskegee University as hallowed ground.

The significance of the university – built by Booker T. Washington, a former slave – is not lost on Stevenson. He has devoted his life to fighting egregious inequality within the criminal justice system, and has spoken at the university many times. Stevenson, the founder of the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) in Montgomery, is often called “America’s Mandela.”

Recently, Stevenson returned to his Tuskegee “stomping grounds” to discuss his book, “Just Mercy.”

“Booker T. Washington created a legacy that is inspiring,” Stevenson said. “We all need to understand his work and life to appreciate what hard work and dedication can achieve. I’m proud that Tuskegee has so thoughtfully honored this legend. We are all the better for it.”

Throughout the years, the university and the Booker T. Washington home have welcomed dignitaries, world leaders and opinion-shapers such as Teddy Roosevelt and Andrew Carnegie. The Tuskegee legacy started with Washington, who, Stevenson agrees, overcame incredible odds in the late 1800s to form the university.

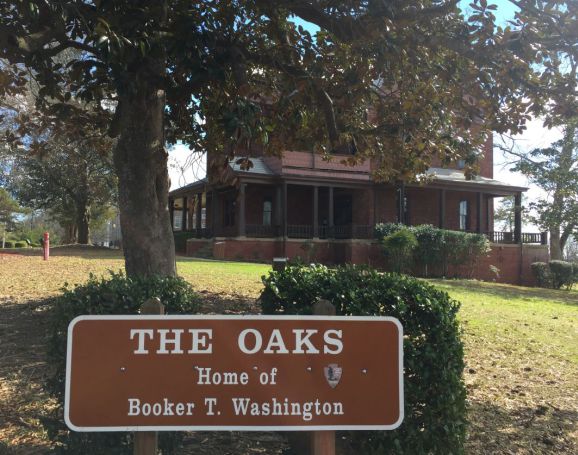

The Oaks is part of Washington’s legacy.

The Oaks, the beautiful 7,800-sq.-ft. red brick home across from Tuskegee University, has always gained notice. Three stories high, the Queen Anne-style home has a wrap-around porch and high ceilings.

Built for Washington in 1899 by the university’s first students, the home is as sturdy as his aspirations for the African-American students who followed him. Designed by Robert Taylor, the first black graduate of MIT, The Oaks was the first modern house in Macon County featuring indoor plumbing and electricity. The beautiful home served as an example of what African-Americans could achieve when allowed an education.

Filled with original and period furniture, The Oaks provides an inside view of Washington’s life there in the early 1900s. Visitors entering the huge mansion can view the Washington family’s parlor, living room and dining room, all which are adorned with European-style, hand-painted frieze murals of a verdant landscape. In the family room, Washington’s daughter, Portia, practiced piano.

Walking up the staircase, visitors touch the handrail used by all of the Washington family: The rail was designed for Washington’s third wife, Margaret, who was under 5 feet tall. Historians believe that paint for the upstairs was invented by George Washington Carver, who used Alabama’s red clay as the base. Margaret and her husband had their own bedrooms, a luxury at that time. A claw-foot bathtub anchors the family bathroom at the right of the hall. At the back of the home, Washington’s office holds his original desk and an ornately carved chair. A green, upholstered chair beside the desk belonged to President Abraham Lincoln. Across from Washington’s desk, his secretary’s desk is preserved.

Shirley Baxter, a park ranger for the National Park Service (NPS), is among those who helps welcome 25,000 visitors yearly to The Oaks. During her career with the Department of the Interior, Baxter has spent 15 of her 32 years in service as a NPS ranger. She knows every nook and cranny of the mansion, as well as the storied history of visiting diplomats.

Baxter said it’s noteworthy that students at then-Tuskegee Institute made the bricks for Washington’s home – a million a year – and built the house in 1899.

Nearly 120 years later, school groups flock to the school in February, in honor of Black History Month.

“Booker T. Washington was the first principal of the school, later becoming the president,” Baxter said. “He came here when he was 25. For 20 years, he was the most influential African-American in the country. He was well-respected. He had the vision to really make it go.”

“Women even went to school here in 1881,” she said. “It was advanced thinking for women to be in school – he wanted them to be prepared to go back home and work.”

Washington’s plan was to train young people to be self-sufficient and to be economically independent. He wanted students to have a school that would enable them to start a business or get a job, and made sure the school taught trade skills to everyone who attended. It was through the development of these trades that the school was built from the ground up.

Washington pushed people to buy land and become self-sufficient: He made it a point to work in his own garden each morning.

Growing up in Missouri, Baxter believes that she’s where she was meant to be in life. Indeed, her office is housed at the George Washington Carver Museum across from The Oaks.

“I read George Washington Carver’s autobiography probably 100 times,” Baxter said. “I loved it.”

She relishes sharing her knowledge about the home with visitors.

“I really enjoy small groups, where you can interact and engage with them,” Baxter said. “You think about the people that were here. It took all these people to make it a success.”

Tuskegee University professor Dr. Rhonda Collier sees the red-brick mansion as a link to the hopes and dreams of her students. She requires her freshman English classes to tour the home.

“I think it gives them a literal and figurative formulation for their career,” said Collier, interim director of Tuskegee University’s Global Office. “It sets the stage for what they can achieve. The house itself embodies those goals, if they embrace the founder’s mission, looking at his life and what former students contributed by building this home.”

Since 2010, Collier has made the visit part of the work for freshman English composition.

“I ask students to identify three personal goals embodied by objects they see in the home,” she said. “It provides a very good introduction to the school and its history. It’s one of those seminal, historic landmarks of the campus.

“The house serves as a reminder to students about the wonderful choice they’ve made to attend Tuskegee University, to imagine the possibilities for themselves,” Collier said.