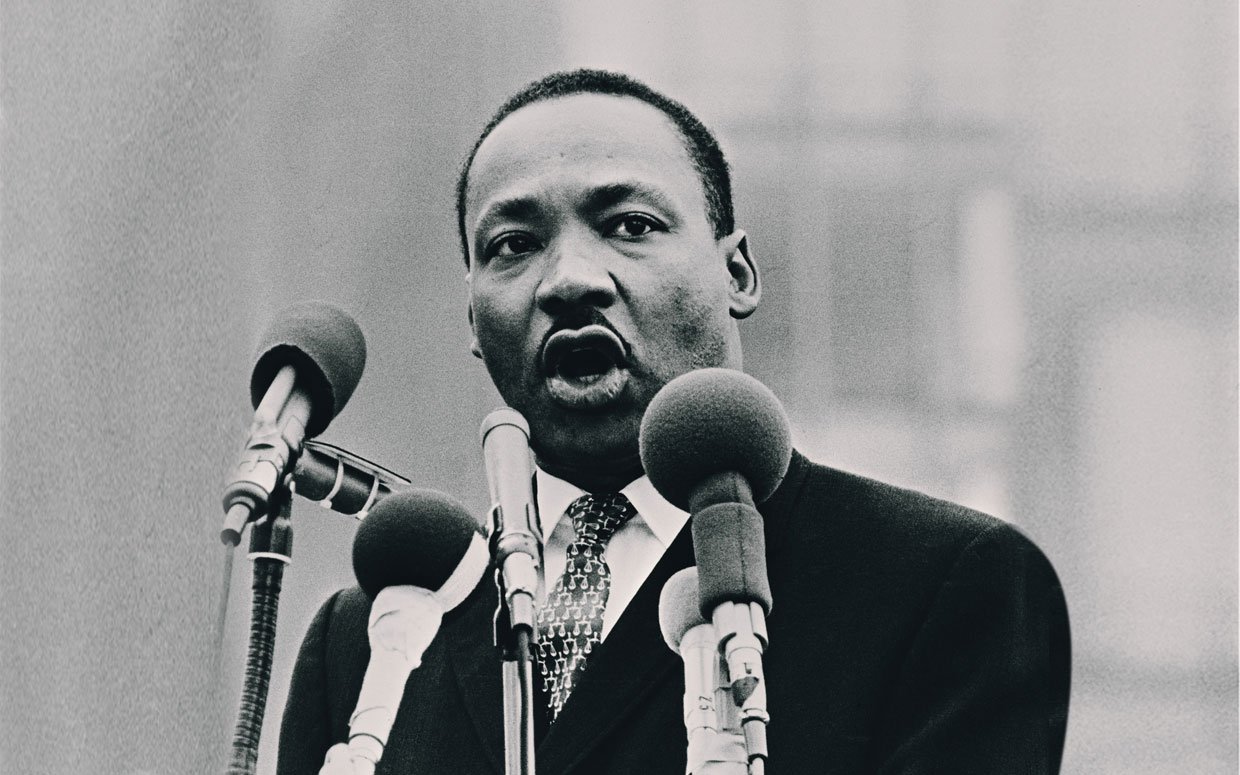

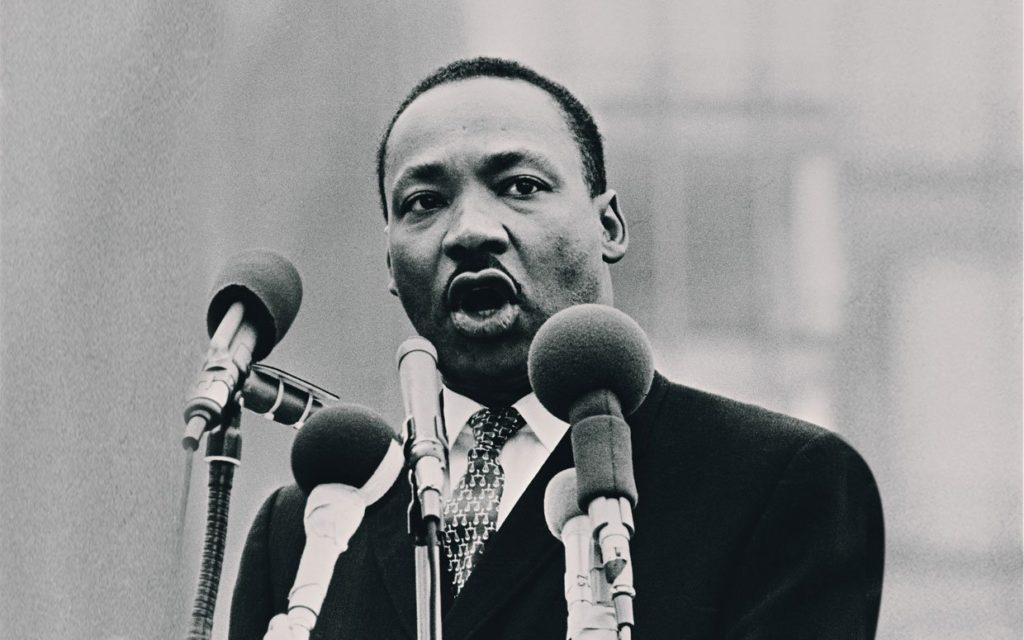

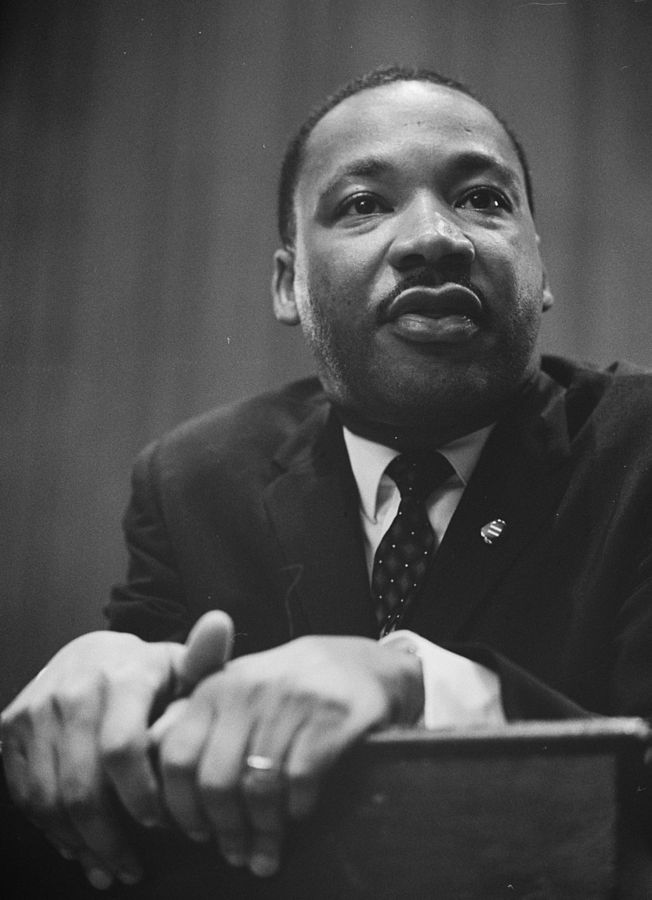

Special to The Times

On April, 2, 1963, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Rev. Ralph David Abernathy and the Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker met at Birmingham’s A.G. Gaston Motel, which would become a key meeting place for the growing Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham, to finalize plans for Project C—for Confrontation: huge, jail-filling, history-making demonstrations, during the Easter season. In this excerpt from her book, The A.G. Gaston Motel in Birmingham: A Civil Rights Landmark, award winning freelance writer Marie A. Sutton recounts events from that period that led to the arrest of Dr. King and inspired him to write what many consider a jewel of American literature — “Letter from Birmingham Jail.”

Although the movement was moving forward, the widespread support of locals was not there. The SCLC wanted the jails of Birmingham to be overflowing with protestors, but that wasn’t happening.

Shelley Stewart, the local rock-and-roll deejay who had devoted black and white listeners, remembered that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Rev. Wyatt Tee Walker, and Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth didn’t wait for people to show up. While at his record store, Shelley’s Record Mart on 1607 Fifth Avenue North, Stewart remembered that King and others came in and bemoaned how difficult it was to get marchers. “Hey, Shelley, I sure need these people to get fired up and march,” King told Stewart. “They won’t come to the meeting.”

But King wasn’t about to let dust gather around his feet. He said, “I am going down to the poolroom.”

“That’s right, the preacher,” Stewart recalled. King and the men headed into the Fourth Avenue District, where there were countless bars, including a shoeshine place where, as quiet as it was kept, you could get whiskey in the back. King went downstairs to the poolroom in the Masonic Temple.

“An hour later, I am turning in front of my store at Seventeenth Street and Fifth Avenue North. I see Martin and about 40 or 50 men following him. They were saying, ‘Freedom! Freedom!’ I said, ‘What in the world?”

Stewart described the sight of King and Wyatt walking in step with winos and “some guys I knew from around the way.”

“What Martin did, he went to the poolroom, restaurant, the bar and down to Rat Killer’s. Everywhere he stopped, he told folks, ‘I need you to stand up for freedom and join me,” Stewart remembered.

King and the group went to the courtyard of the Gaston Motel. King climbed up the stairs and faced the men so that the group could see him. “Can y’all get double what we have?” he asked them.

“He took winos and guys who were on the block. They were there when others wouldn’t come,” Stewart recalled. “That’s what it was all about. In that parking lot, that inspired me to do something that came after that.”

It inspired Stewart to do his part, to use the airways to encourage people to stand up for freedom.

Outsider

But the tensions between King’s group and those who felt he was out of line for stirring up trouble had grown. Religious leaders, political influencers and the like were speaking out against King, describing him as an outsider. Many felt the segregation issue should be handled in the courts and that he was stirring up people. They thought a protest on Easter Sunday was out of line.

On April 8, King met with local black leaders at the Gaston Building so that he could make an appeal and hopefully gather support for his planned protest. It turned out to be a showdown instead. Later that night, in response, Rev. Ralph David Abernathy gave a biting sermon at First Baptist Church of Ensley. The Cleveland Call and Post wrote that he “scathingly assailed the black ‘bourgeoisie’ to the howling delight of the rafter-packed audience.”

“Talk to your doctor, your lawyer, your insurance man and withdraw your trade from him if he is not with the movement,” Abernathy told them.

A.G. Gaston’s statement

The next day, April 9, Gaston released a statement to the Birmingham World that sent movement people through the roof:

I regret the absence of continued communication between the white and Negro leadership in our city and the inability of the white merchants and white power structure of community to influence the City Fathers to establish an official line of communication between the races in our city.

This condition, along with many unsolved bombings and other incidents causing unfavorable publicity for Birmingham has made this city a very attractive target for the present unhappy situation in which we now find ourselves.

There is no doubt in my mind or in the minds of any of us, concerning the aspirations of the Negro citizens in this community and throughout the country. We want freedom and justice; and we want to be able to live and work with dignity in all endeavors where we are qualified. We also want the privilege of access to those facilities that will make an individual qualified. We also want to contribute our share for the progress our community. I believe we have capable and intelligent leadership among the colored people in the community, competent and able to work toward bringing the hopes, dreams and aspirations of the Negro citizens to reality.

The problem that Birmingham now faces were faced by other great Southern cities, and, to the credit of these great cities, which lie within a short distance of us, the local leaders in their communities got their minds, talents and energies together and solved their respective problems.

Today, Birmingham now stands on the threshold of transition to greatness. The sails have been set for the City and it is now incumbent on the leadership of this community to chart its destiny.

I therefore call upon all the citizens of Birmingham to work harmoniously and together in a spirit of brotherly love to solve the problems of our city, giving due recognition to the local colored leadership among us.

A.G. Gaston, Sr.

‘Super Uncle Tom’

This was seen by King as a slight to him and the other non-locals. Shuttlesworth was fuming. He had moved to Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1961 but was still leading the Birmingham movement. The “locals” remark seemed like an attack. He accused Gaston of being “a Super Uncle Tom” and claimed that he charged too much for his rooms at the motel.

People were considering protesting Gaston and his businesses, but Ed Gardner, a local minister and Gaston advocate, warned that if the group proceeded, he and his group of ministers would run them out of town.

Soon afterward, Shuttlesworth retracted his statement and apologized. In order to bring the groups together, King set up an advisory committee of 25 men and women who would meet daily in the Gaston Motel to be briefed on the day’s events.

A crossroads

On April 10, Public Safety Commissioner Eugene “Bull” Connor got an injunction that made it illegal for protestors to march. It also raised the bail amount to four times its original, from $300 to $1,200. Connor vowed, “You can rest assured that I will fill the jail full of any persons violating the law as long as I’m at city hall.” Now the movement was at a crossroads. Would it proceed with planned protests and break the law? Also, raising the bail amount meant protestors needed more money. Their biggest fundraiser, King, didn’t need to be arrested. He needed to raise more funds. But the people who had volunteered to go to jail were looking for their leader to follow them there.

‘A Group of Clergymen’

To add to that, on April 12, which was Good Friday, eight clergy in Birmingham posted a statement in the Birmingham News noting that the march was “unwise and untimely.” They urged “our Negro community to withdraw support from these demonstrators, and to unite locally and work peacefully for a better Birmingham.” The men included the Right Reverend C.J. Carpenter, Episcopal bishop of Alabama; Reverend Joseph A. Durrick, auxiliary Roman Catholic bishop; and Rabbi Hilton Grafman of Temple Emanuel.

From “A Group of Clergymen” published in the Birmingham News

We clergymen are among those who, in January, issued “an Appeal for Law and Order and Common Sense,” in dealing with racial problems in Alabama. We expressed understanding that honest convictions in racial matters could properly be pursued in the courts, but urged that decisions of those courts should in the meantime be peacefully obeyed.

…We are now confronted by a series of demonstrations by some of our Negro citizens, directed and led in part by outsiders. We recognize the natural impatience of people who feel that their hopes are slow in being realized. But we are convinced that these demonstrations are unwise and untimely.

…Just as we formerly pointed out that “hatred and violence have no sanction in our religious and political traditions,” we also point out that such actions as incite to hatred and violence, however technically peaceful those actions may be, have not contributed to the resolution of our local problems. We do not believe that these days of new hope are days when extreme measures are justified in Birmingham.

…We further strongly urge our own Negro community to withdraw support from these demonstrations, and to unite locally in working peacefully for a better Birmingham. When rights are consistently denied, a cause should be pressed in the courts and in negotiations among local leaders, and not in the streets. We appeal to both our white and Negro citizenry to observe the principles of law and order and common sense.

‘Alone in a crowded room’

“Martin was particularly disturbed when he read it, shaking his head and wondering how religious leaders could encourage the kind of attitude that had created a city where bombing of black houses and churches had become almost a common occurrence,” Abernathy wrote. “He brooded about the statement long after he should have dismissed it from his mind.”

As a result, shortly after that, King’s own advisory committee also asked him not to march. “They cited the need to obey the law and their own belief that things might get out of hand, that perhaps we needed a cooling off period; that it would be improper to violate the sanctity of the Easter season by acts of disobedience that might provoke violence,” Abernathy wrote.

All twenty-five of them met in the Gaston suite to discuss the different arguments. “So we sat there in the motel suite and for a while allowed them to lecture us on the virtues of prudence and compromise,” Abernathy wrote.

At the same time, a crowd was gathering in Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, where King’s staff was getting them ready, “taking away their guns, knives and razors and telling them that they must learn to cover their heads and never strike out, even when attacked.” King remembers having to decide on that Good Friday whether to walk outside the motel to march and surely be arrested.

“No one knew what to say, for no one knew what to do,” King wrote. “I was alone in that crowded room.”

King dismissed himself, went to the back of the suite and stood at the center of the floor, he said.

“I think I was standing at the center of all that my life had brought me to be,” King wrote. “I thought of the Birmingham Negro community, waiting.

‘Red Sea of injustice’

Then my mind leaped beyond the Gaston Motel, past city lines and state lines, and I thought of the twenty million black people who dreamed that someday they might be able to cross the Red Sea of injustice and find their way to the Promised Land of integration and freedom. There was no more room for doubt.”

He changed into “work” clothes and went back to the crowd waiting. “I don’t know what will happen; I don’t know where the money will come from. But I have to make a faith act,” he told them. King walked up to Abernathy and told him that he was going to march.

He said that his father could be there for his Atlanta congregation on Easter, but since Abernathy had no one to cover his church service on that day, he should go back to Atlanta.

“Then he reached out and embraced me,” Abernathy wrote. “I knew what he was thinking: He might either be arrested and jailed for months or else be killed, given the pent-up emotions about to be loosed.

“He was giving me a way out,” Abernathy continued. “But on this Good Friday, I wasn’t about to be Peter.”

Abernathy declared that he would be joining King.

King linked arms with the others, and right there in the room, they sang in unison “We Shall Overcome.”

Birmingham Jail

Later that day, King and Abernathy were arrested. They were put in separate jail cells, and for the first twenty-four hours, King was put in solitary confinement and not allowed any communication. “No one was permitted to visit me, not even my lawyers,” King wrote. “Those were the longest, most frustrating and bewildering hours I have lived.”

King worried about his fellow marchers and his wife, Coretta, who had just given birth to their youngest child, Bernice. He didn’t know what his arrest was doing to the morale of the people.

He had many questions.

“You will never know the meaning of utter darkness until you have lain in such a dungeon, knowing that sunlight is streaming overhead and seeing only darkness below,” King wrote.

President John F. Kennedy was alerted of King’s arrest, and he moved mountains to arrange for the minister’s wife to call him. Also, King’s attorneys, Arthur Shores and Orzell Billingsley, received permission to visit him. Not long after that, his friend and lawyer Clarence Jones from New York came for a visit. He told King that actor/singer Harry Belafonte had raised $50,000 for the bail money and had said, “Whatever else you need, he will raise it.”

Those words “lifted a thousand pounds from my heart,” King wrote.

April 14, Easter Sunday, arrived, and kneel-ins took place at white churches across the city.

While in jail, King penned a response to the clergy who had written to him earlier. He started writing it in the margins of a newspaper, then on scraps of paper and finally in a notebook he was able to attain. Wyatt got the letter and pieced it together in the Gaston Motel.

Dr. King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail” is considered the preeminent document of the civil rights movement. Read the letter by clicking here.

MLK Weekend EventsDr. Martin Luther King Jr. Celebration Fri. Jan. 13, 2017 3:30 p.m. Smithfield Branch Library (1 8th Ave. W. Birmingham, Ala. 35204) The Birmingham Public Library’s Smithfield Branch, one of Alabama’s first libraries for the state’s black population, is celebrating Dr. King’s legacy by screening a film about his campaign for equal voting rights. The event is free to the public. For more information, call 205-324-8428.

MLK Day 5K Drum Run-Birmingham Sat. Jan. 14, 2017 Registration begins at 7 a.m., race starts at 8 a.m. Birmingham Civil Rights District (1600 5th Ave. N., Birmingham, Ala., 35203) The MLK Day 5K Drum Run/Walk, presented by Leftover Energy, LLC, will feature race participants of all backgrounds, demographics, races, and genders coming together in unity. The race will begin and finish in Kelly Ingram Park, and drumlines from the schools around the Birmingham metro area will line up along the race course to keep racers motivated. Registration fees are $30. Call 404-545-3732 or email leftoverenergy@gmail.com.

Reflect and Rejoice: Letter from Birmingham Jail Sun. Jan. 15, 2017 3 p.m. Alys Robinson Stephens Performing Arts Center (1200 10th Ave. South, Birmingham, Ala. 35294) The Alabama Symphony Orchestra, in partnership with the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, presents its annual celebratory concert honoring King’s life and legacy. The orchestra is joined by actor Brandon McCall from the Red Mountain Theatre Company for a presentation highlighting King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” The event will also feature a 100th anniversary of jazz musician Scott Joplin’s death including a performance by soprano Allison Sanders. Call 205-975-2787 or visit http://alabamasymphony.org/ReflectRejoiceMLK2017.html for more information.

14th Annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Memorial Lecture: “The First Step: A Conversation on Islam in America” Sun. Jan. 15, 2017 3 p.m. Linn-Henley Research Library (2100 Park Place, Birmingham, Ala. 35203) The Birmingham Public Library and the Birmingham Islamic Society join together to host a discussion on the experience of being a follower of the Islamic faith in the U.S. The talk will take place in the Arrington Auditorium on the fourth floor of the Linn-Henley Research Building. Call or email Jim Baggett at 205-226-3631 or jbaggett@bham.lib.al.us for more information.

U.S. Attorney General Loretta E. Lynch Sun. Jan. 15, 2017 3 p.m. 16th Street Baptist Church (1530 6 th Ave N. Birmingham, AL 35203 Attorney General Loretta E. Lynch will deliver the final speech of her tenure as attorney general. Open to public and press.

31st Annual MLK Unity Breakfast Mon. Jan. 16, 2017 7:30 a.m. North Exhibition Hall, BJCC (2100 Richard Arrington Blvd. N., Birmingham, Ala. 35203) U.S. Rep. Terri Sewell will act as the keynote speaker at the 31st Annual MLK Unity Breakfast. For more information, call 205-938-4MLK or email breakfast4unity@gmail.com.

Birmingham Civil Rights Institute-Free admission for Martin Luther King Jr. Day Mon. Jan. 16, 2017 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. Birmingham Civil Rights Institute (520 16th St. N., Birmingham, Ala. 35235) The BCRI Galleries are open to the public with no charge at 9 a.m.

MLK Track & Field Invitational Mon. Jan. 16, 2017 8 a.m. Birmingham CrossPlex (2337 Bessemer Rd., Birmingham, Ala.) Birmingham City Schools is hosting the MLK Track & Field Invitational, hosted at the Birmingham CrossPlex. The event will include 2,000 high school athletes. Call 205-279-8900 for admission prices.

Hands On Birmingham’s MLK Jr. Day of Service Mon. Jan. 16, 2017 All day Hands On Birmingham continues its tradition of giving back to Birmingham and surrounding areas. Volunteers are needed to help clean up Birmingham’s parks, Smithfield Estates, Huffman Middle School, Fairfield, the Salvation Army, McDonald Chapel, Hoover Senior Center, and more. Visit http://www.handsonbirmingham.org/MLK, call 205-251-5849 or email info@handsonbirmingham.org for full list of volunteer opportunities.

Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day Parade Mon. Jan. 16, 2017 12 p.m. – 1 p.m. Birmingham City Hall (710 20th St. N., Birmingham, Ala. 35203) Pastor Mike McClure, Jr. will lead the Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Day Parade, starting at Birmingham City Hall and ending at the 16th St. Baptist Church.

YouthServe MLK Day of Service Mon. Jan. 16 2017 10 a.m. -2 p.m. Bethel Baptist Church (3200 28th Ave. N., Birmingham, Ala., 35207) YouthServe Inc. is recruiting 13 to 18-year-olds and their families to volunteer in the Collegeville Community. Volunteers will clean up, paint, landscape while learning more about the part Bethel Baptist Church had in the Civil Rights movement. Volunteers will end the day by discussing the connections between people in Birmingham and beyond. Lunch will be provided. Call 205-521-6651 or visit https://www.eventbrite.com/e/youthserve-mlk-day-of-service-tickets-29997313773 to register. |