By Erin Harney

Alabama NewsCenter

The National Park Service (NPS) turned 100 years old this year. Over the past century, the organization has grown from 35 national parks to more than 400 sites under the protection of the NPS today. From national seashores, monuments, heritage and historic sites, trails and military parks, the variety is as vast as the history they contain. There are nine National Park Service sites in Alabama that drew 790,000 visitors with a $31 million economic impact last year. Alabama NewsCenter is spending the rest of this centennial year highlighting each Alabama site.

Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail

The Selma to Montgomery National Historic Trail was established as a National Park Service site by Congress in 1996, to commemorate the 54-mile peaceful march from Selma, Alabama to the state Capitol in Montgomery in March 1965.

The march, along with an unsuccessful attempt two weeks earlier that became known as “Bloody Sunday,” successfully brought attention to the injustices that had blocked African-Americans from voting. The marches spurred President Lyndon Johnson to sign the Voting Rights Act, “which suspended literacy tests, called for the appointment of federal election monitors, and directed the U.S. attorney general to challenge the use of poll taxes by states,” said the NPS.

The route is also designated as a National Scenic Byway/All-American Road.

Brief history of the Selma to Montgomery March

While the 15th Amendment, ratified in 1870, stated that no U.S. citizen should be denied the right to vote “on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude,” almost 100 years later, counties in Alabama were blocking African-Americans from registering to vote. According to the NPS, in the early 1960s, “no African-Americans were registered to vote in Lowndes County and only 2 percent of Dallas County African-Americans were able to vote.”

In the decades leading up to the 1965 turning point, civil rights activists in national, state and local organizations worked tirelessly to achieve equality for African-Americans. A significant part of the movement centered on voting rights. Without the ability to vote, African-Americans had no voice in leadership or the laws by which they had to live.

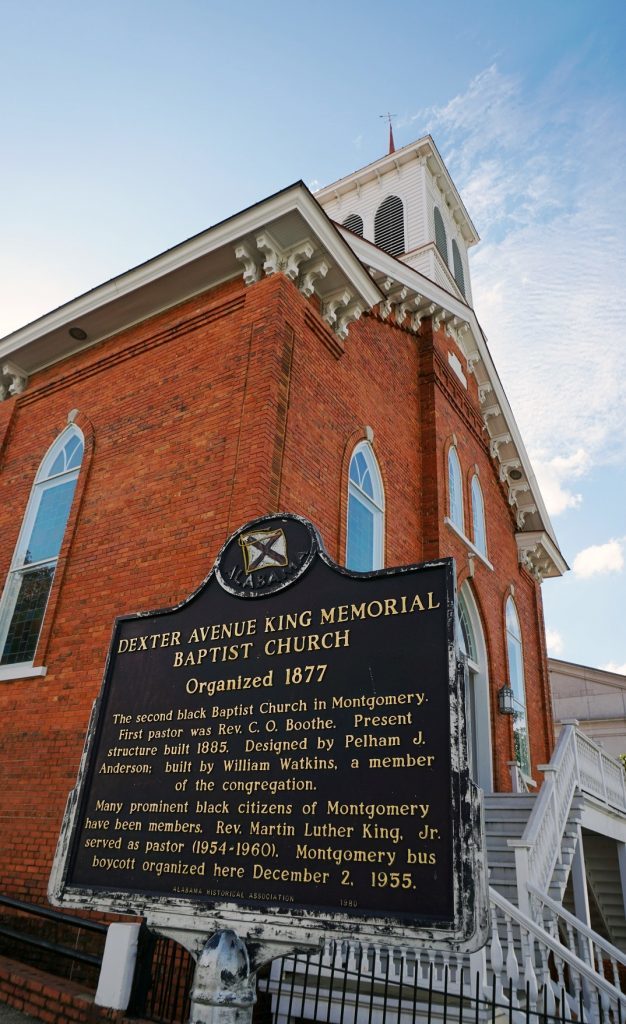

“Dr. (Martin Luther) King believed deeply in the principle of ‘nonviolent direct action’ as the most effective and morally justified strategy for social change,” said the NPS. Alabama activists adopted these principles, organizing sit-ins, rallies and marches.

On Feb. 18, 1965, during a night march in Marion, Alabama, Jimmie Lee Jackson, a demonstrator who was 26 years old, was shot by an Alabama state trooper. He died from his wounds on Feb. 26.

On March 7, in memory of Jackson, 600 nonviolent protesters departed from the Brown Chapel A.M.E. Church in Selma, intent on marching to the Capitol in Montgomery. As the protesters crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, Alabama State Troopers stopped them and gave them two minutes to disperse. Before the two minutes expired, the troopers attacked the marchers. The attack continued into the night in the streets of Selma. Media outlets captured the violence and brought much-needed attention to the reform movement. That Sunday became known as “Bloody Sunday.”

Following “Bloody Sunday” an injunction was issued against another march to Montgomery. So, on March 9, two days after the violence, 2,000 people crossed the Edmund Pettus Bridge, kneeled where the violence had taken place on Sunday, and then turned around.

The injunction was lifted a week later, following Johnson’s request for Congress to pass a voting rights bill. In his address, the president said, “To those who seek to maintain purely local control over elections — the answer is simple. Open your polling places to all your people. Allow men and women to register and vote whatever the color of their skin. Extend the rights of citizenship to every citizen of this land. There is no constitutional issue here. The command of the Constitution is plain. There is no moral issue. It is wrong — deadly wrong — to deny any of your fellow Americans the right to vote in this country. There is no issue of states’ rights or national rights. There is only the struggle for human rights.”

Alabama Gov. George Wallace vowed to stop a march to Montgomery, but Johnson federalized “1,900 Alabama National Guard troops and sent 2,000 soldiers and dozens of FBI agents and federal marshals” to protect the marchers, the NPS said.

On March 21, about 4,000 marchers set out from Selma toward Montgomery. A core group of about 300 made the full 54-mile journey, and upon reaching Montgomery, were joined by supporters, to form a group of 25,000. “This time no state troopers blocked the way. A marcher carried an American flag to Montgomery, where the Confederate flag flew over the Capitol,” said the NPS.

On Aug. 6, 1965, Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act. “By 1966 the number of registered African-Americans in Alabama was four times the number of 1960,” said the NPS.

Driving the Historic Trail

The National Park Service (NPS) recommends starting the trail in Marion, where Jackson was shot, as his death was the catalyst for the Selma to Montgomery March. There is an NPS marker at the Zion United Methodist Church (3087 Pickens Street, Marion, AL 36756). Marion was added to the National Historic Trail in 2015.

National Historic Trail Route signs will lead visitors from Marion to Selma, where the Selma Interpretive Center is located. A museum display at the visitor center exhibits Selma’s role in the civil rights movement and provides a brief history of the events leading up the march.

From there, visitors will cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge, following U.S. Highway 80 to White Hall, where the Lowndes Interpretive Center is located. This visitor center has an exhibition and video that displays the struggles and success of the march, as well as the long-term effect the march had on civil rights in the United States.

The trail continues along U.S. 80 to the Alabama State Capitol in Montgomery, where 25,000 marchers converged in support of equal voting rights for all.

The trail can be driven every day of the year. Both interpretive centers are open Monday through Saturday from 9 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. and are closed on Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s Day.

The Selma Interpretive Center is at 2 Broad St., Selma, AL. For more information call 334-872-0509.

The Lowndes Interpretive Center is at 7002 U.S. Highway 80 West, White Hall, AL. For more information call 334-877-1983.

Upcoming events:

Next year, the 52nd Selma Bridge Crossing Jubilee will be held March 2-5. The jubilee is billed as the “largest annual civil rights commemoration event in the country.” For more information about this event, call 334-526-2626 or visit selmajubilee.com.