By Ariel Worthy

The Birmingham Times

When it comes to capital punishment in America, blacks are nearly four times more likely to receive the death penalty than other races.

In 2015, 49 people received death sentences. Twenty-one were black, 16 were white and the rest were of other races. In Alabama, six death sentences were given, and four defendants were black.

A previous study by the Death Penalty Information Center found that the odds of receiving the death penalty are nearly four times (3.9) times higher if the defendant is black.

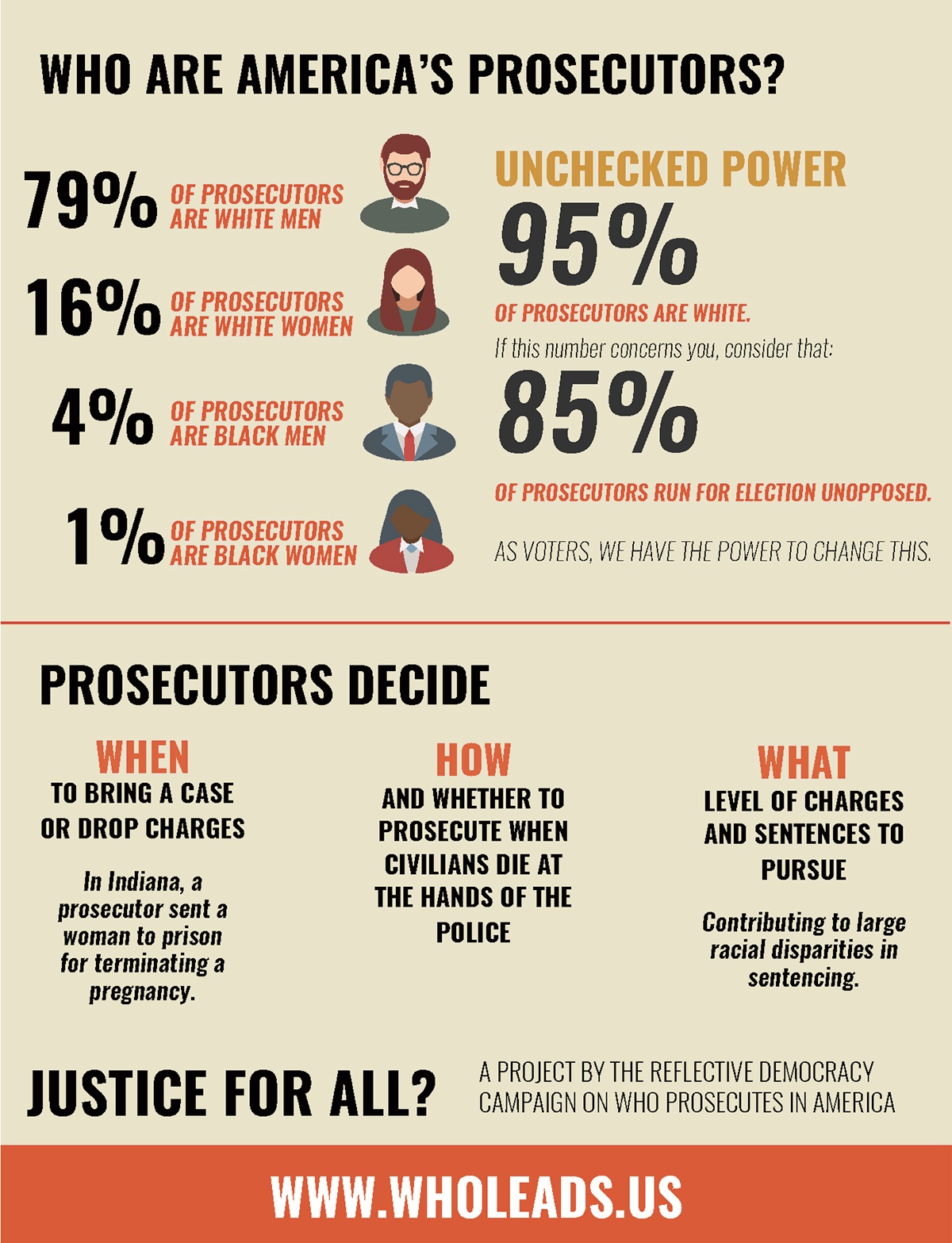

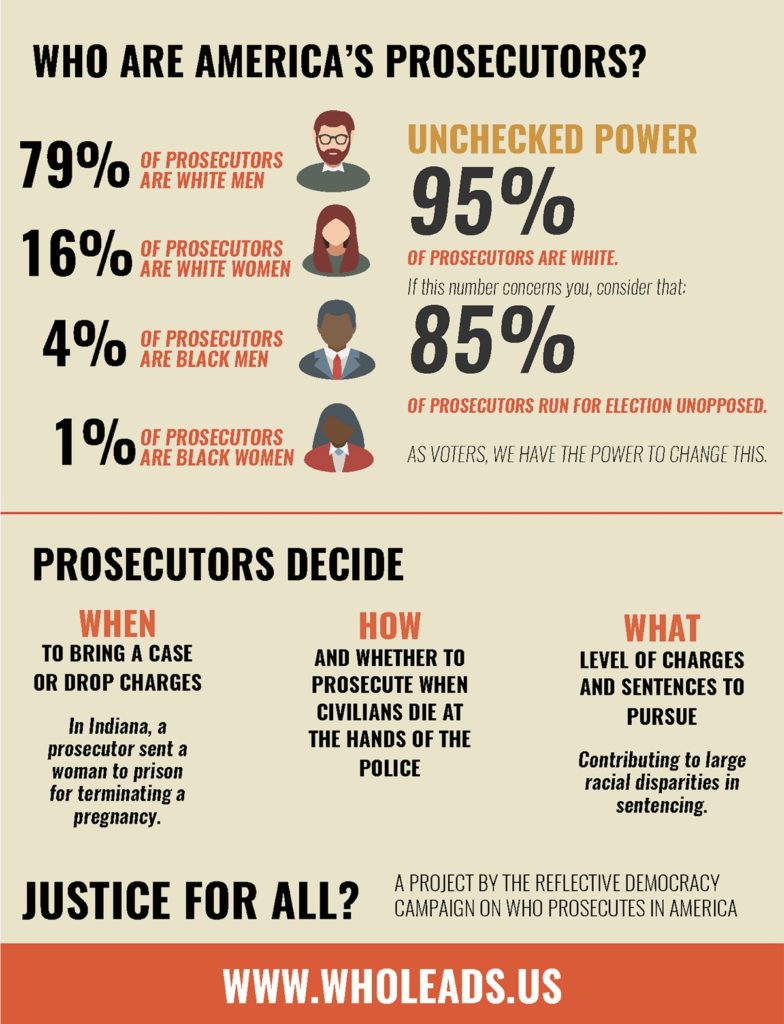

The lack of minorities in the legal decision-making process is one argument why the death penalty is racially skewed. In the United States, 79 percent of prosecutors are white men, 16 percent are white women; only 4 percent of prosecutors are men of color, and 1 percent are women of color. That makes 95 percent of the decision-makers white.

According to the study, prosecutors are key decision-makers in what level of charges and sentences are pursued. This can contribute to large racial disparities in sentencing.

Who are the decision-makers?

The death penalty could be sought after more than it actually is, particularly with other races, but often it is not. One of the likely reasons for this discrepancy is that almost all the prosecutors making the key decision about whether a person will live or not are white. Only 1 percent of the District Attorneys in death penalty states are black, and only 1 percent are Hispanic. The remaining are white, and almost all are men. In Alabama, of 41 district attorneys in the state, only one is black.

Another problem in prosecution is procedure. When a prosecutor is faced with a crime in his community, he often consults with the family of the victim as to whether the death penalty should be sought. If the victim’s family is prominent, white, and likely to support him in his next election, there may be a greater chance for the death penalty to take place, according to the study.

Those who die because in these situations are not the individuals who usually evoke the public’s sympathy. While they have committed horrendous crimes, but crimes are no less horrendous by white offenders or against black victims, yet those killers are often spared death.

Racism in court

Also, racial slurs aren’t a thing of the past in courtrooms. Blatant racism can be seen and heard often in courts around the country. According to Deliberate Indifference: Judicial Tolerance of Racial Bias in Criminal Justice by Bryan Stevenson and Ruth Friedman, a prosecutor in Alabama gave as his reason for striking several potential jurors the fact that they associated with Alabama State University, an Historically Black University in the state.

In January, Superior Court Judge Roger Bradley of Georgia stepped down after being investigated for using a racial slur in open court.

“When I first moved up to this county in 1974, I was actually introduced to a fellow who lived right here behind the courthouse and he referred to himself, as did everybody else in town, not in a disparaging manner, as (n-word) Bob,” the judge said.

Severity of crimes

Murder cases become death eligible through certain aggravating factors which make one murder “worse than another.” The prosecutor is supposed to consider the presence of such factors as whether a murder was committed with grave risk to the life of others, whether the murder was committed in the course of another serious crime such as robbery or rape, whether torture was a factor, or whether the defendant had a significant violent history. The jury is similarly told to consider those factors when deciding whether the sentence should be life or death, once a guilty verdict is decided.

The race of the defendant is not supposed to influence whether a person is sentenced to death, but often it is a determining factor in whether a defendant will receive the penalty.

Race of the victims

The racial combination was most likely to result in a death sentence if the defendant was black and the victim was of another race, regardless of how severe the murder was committed, according to the study. Black-on-black crimes were less likely to receive a death sentence, followed by crimes of other defendants, regardless of the race of their victims. Few defendants of any race are likely to get the death penalty in a case involving defendants with no prior record and where the killing may have been accidental. The bulk of crimes in mid-range severity, blacks who kill non blacks are more likely to receive the death penalty than blacks who kill blacks, and they have death sentencing rate much larger than the rate for defendants of other races who commit similarly severe murders of black victims.