By Charles Buchanan

UAB Magazine

At Birmingham’s First Presbyterian Church, they sat as the congregation did that day when two African-American women appeared for the holiday service. The city was on edge from nearly a week of protests, and senior pastor Edward Ramage had not preached racial integration from the pulpit, but he did not hesitate to welcome the visitors, unlocking the sanctuary doors that barred them from entering. As current pastor Shannon Webster told the story and pointed out the pew up front where the women had sat, it was easy to imagine them taking an anxious but determined walk down the aisle amid hundreds of staring white faces.

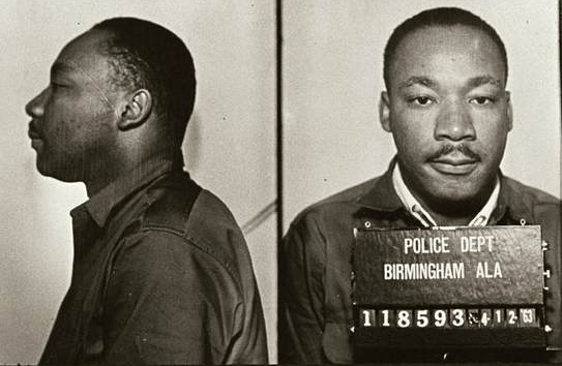

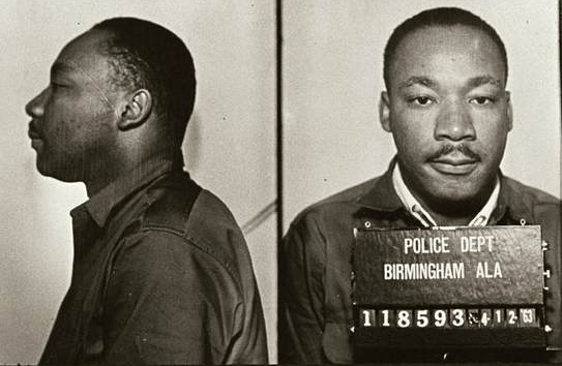

The tour, led by students Graham Palmer and Tyler Heatherly, paused on the steps of the Cathedral Church of the Advent. Ramage’s actions took courage—indeed, a large number of his parishioners promptly walked out, and he later received death threats. But for a frustrated Martin Luther King Jr., scribbling on scraps of paper in a local jail cell a week later, Ramage was only taking baby steps to advance the cause of racial equality and justice. Soon, King would address his “Letter from Birmingham Jail” to Ramage and seven other local clergymen, tying them all together “in a single garment of destiny” that would change the course of the civil rights movement.

The tour, which stopped at five other churches, one synagogue, and one parking lot, added dimensions to the famous letter, revealing how the eight pastors and one rabbi prompted King to write—and how they handled the repercussions. But for the UAB students who developed and led the walk, it also was the culmination of a course that gave them an entirely new way to look at the past.

“Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere. . . . Shallow understanding from people of good will is more frustrating than absolute misunderstanding from people of ill will. Lukewarm acceptance is much more bewildering than outright rejection.” — Martin Luther King Jr., “Letter from Birmingham Jail”

Eye of the storyteller

History comes in two flavors, says Pamela Sterne King, assistant professor and director of the undergraduate program in the UAB College of Arts and Sciences Department of History. Academic history, typically published, is aimed at professional scholars. “Public history,” on the other hand, is much more freewheeling, targeting a wider, more diverse audience that includes pretty much everyone. And it appears in a multitude of shapes: markers and memorials, oral recordings, historic preservation, museums and exhibits, and national parks, to name just a few.

In her HY 481/681 Public History course, Sterne King helps students to get a handle on the subject. And then they make some public history themselves—in this case, the Letter from Birmingham Jail tour.

The walking tour took place on April 16, the 53rd anniversary of the day that King wrote his famous letter.

The first thing students discover is that not all public history is created equal. So much depends on who’s telling the story, what parts of the story they choose to include, and sometimes who’s funding the storytelling project, Sterne King says. Looking around Birmingham, for instance, it’s easy to grasp the city’s industrial beginnings and overall civil rights history, but tough to find plaques or memorials mentioning women, she says. “You come away, at least subconsciously, assuming that women didn’t do anything” in Birmingham’s past, which is a “terrible omission,” she explains.

Why does this matter? Because public history “helps to create and promote a city’s identity,” says Paige Estefan, a history master’s student from Fairhope, Ala., who took King’s course. Think of places like Philadelphia or Savannah, or Nashville or New Orleans. Each city’s image intertwines with its history. In addition, heritage tourism has become big business, attracting visitors who boost local economies as they travel to museums or historical sites.

Balancing the past

In the classroom, Sterne King and her students examined ways in which cities present their stories. They also met local historians from the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute and the Birmingham Black Radio Museum, getting a glimpse of potential careers in the field. Sterne King also shared her own path through public history: She was the first historic preservationist for the city of Birmingham and has played key roles in a multitude of downtown and neighborhood historic revitalization projects.

A recurring topic of discussion focused on the public’s changing interpretations of patriotism and nationalism, which affects how people view the past in different eras. Case in point: the ongoing controversies concerning the display of Confederate memorials and monuments across the South. In Birmingham, discussions have focused on the 111-year-old Confederate Soldiers and Sailors Monument in downtown’s Linn Park and the Jefferson County Courthouse’s 1929 murals depicting African Americans picking cotton and doing industrial labor under the watchful eyes of white people. “People get mad on both sides of that topic,” Sterne King says, “because there’s not just one story.” (In May 2016, the Jefferson County Commission decided to keep the murals but hide them from view behind retractable curtains.)

Public history is “a balancing act” that must take into account the community’s current views on a subject, says Robert Austin, a senior history major from Oneonta, Ala., in Sterne King’s class. “You want to try to challenge some widely held beliefs to show that there is more to the story, but you also want to attract the public.” And researching historical events can lead to different opinions and interpretations, he adds. “Whose version of history is more valid? I am not sure there is an answer to that question.”

about 40 and their UAB student guides soon found themselves reliving another spring morning—Easter Sunday 1963.

Walking the lines

With the walking tour, the students started from scratch. “Their job was to figure out what we need to highlight—to decide the points they want to make about the ‘Letter from Birmingham Jail’ and how to illustrate those,” Sterne King explains. One group of students researched the eight clergymen and the congregations they led; another concentrated on developing the photos, maps, text, and scripts needed for the tour and an accompanying brochure.

For a document that outlined the moral foundations of the fight against segregation and is quoted by civil rights leaders and school children worldwide, the letter surprisingly hasn’t received the attention that other moments from the 1960s have, Sterne King says. (A historical marker was placed at the jail site only in 2013.) That surprised Estefan, who helped to organize the student groups, researched and wrote the tour introduction, and filmed the event. “The letter has had a lasting effect on Birmingham; it really shook things up here,” she says.

The students focused on the eight clergymen whom the letter addressed—not only because they spurred King to write it, but also because they were community leaders who represented an audience the civil rights leader desperately wanted to reach: white moderates. The seven pastors and one rabbi all opposed racial intolerance. But they also wanted to help keep the peace in a powder keg of a city. Coming together, the clergymen wrote “A Call for Unity,” a statement publicly criticizing the protest tactics of the civil rights movement and advising patient change through the courts. The jailed King wrote the iconic letter in response, and in it, he “calls them to the mat to tell them they are worse than the Ku Klux Klan,” notes Austin, who helped conduct research for the tour. King “saw the white moderate faction as more interested in order than justice. He takes the moral high ground and lays down the gauntlet: You are either with us or in our way. No more half measures. You can imagine how that type of rhetoric might insult a member of the white community who already felt he had taken big risks in order to support integration.”

At each site on the walking tour, the student guides described the letter’s effect on the men and their congregations. Most, understandably, were upset by King’s remarks. Milton L. Grafman, rabbi of Temple Emanu-El, worried that the letter branded him a bigot, but continued to support racial and religious inclusion. Ramage, deeply affected by King’s words, maintained a commitment to integration in spite of church and community bullying and, suffering poor health, left the city later in 1963. Pastor Webster noted that First Presbyterian now embraces Ramage’s example, inspiring both its ministry and outreach efforts. Perhaps the most poignant stop was the empty parking lot on the corner of 6th Avenue North and 22nd Street, once home to the large, turreted Birmingham First Baptist Church. Its Reverend Earl Stallings, who also welcomed African-Americans on Easter Sunday 1963, became a target for both segregationists and integrationists, and he left Alabama two years later. In 1970, the church split over the prospect of admitting African-American members; in the following decade, the remaining congregation moved, and the building was demolished.

Ground truths

Sterne King plans to make a self-guided version of the Letter from Birmingham Jail tour available to members of the public and city visitors. With support from the Rita P. Kimerling Public History Endowment in the Department of History, she will publish a professionally designed brochure and map based on the students’ work that can be distributed around the city and state. She hopes it will be the first of a series of new heritage tours created by her students. Future installments might focus on “bad women” or Communism in the city’s history.

“Anyone who studies history knows it’s all about controversy,” Sterne King says. For example, “it’s well documented that Birmingham had the largest Communist party in the South, but most people in the community now don’t know that.” That level of historical detail comes naturally with exploring the city block by block, she adds. “It changes your perspective.”

The course certainly has changed her students’ perspectives on their subject. Estefan, nurturing a newfound passion for urban exploration and photography, says the class has helped her fall in love with Birmingham and changed how she studies the past. “Public history is hands on,” she says. “I get to see and physically experience everything that I have researched and read about, which is so gratifying.”

Austin, who wants to teach high school, “hopes to impress upon my students that history is more than just dates and events.” Reflecting upon Martin Luther King Jr., the eight clergymen, and the letter that forever links them, he adds, “history is the story of people and how they lived—their relationships and how they interacted with one another.”