By Solomon Crenshaw Jr.

For The Birmingham Times

Kenneth Whitehead didn’t even get his bus ticket.

By Alabama state law, a convicted felon released from prison is supposed to receive a $10 check and a bus ticket to wherever he or she wants to go. But after completing 13 years of a 20-year sentence for armed robbery and being released in April Whitehead said he didn’t receive a check or a bus ticket.

“They sold out of bus tickets,” said the 36-year-old. “I never heard of that.”

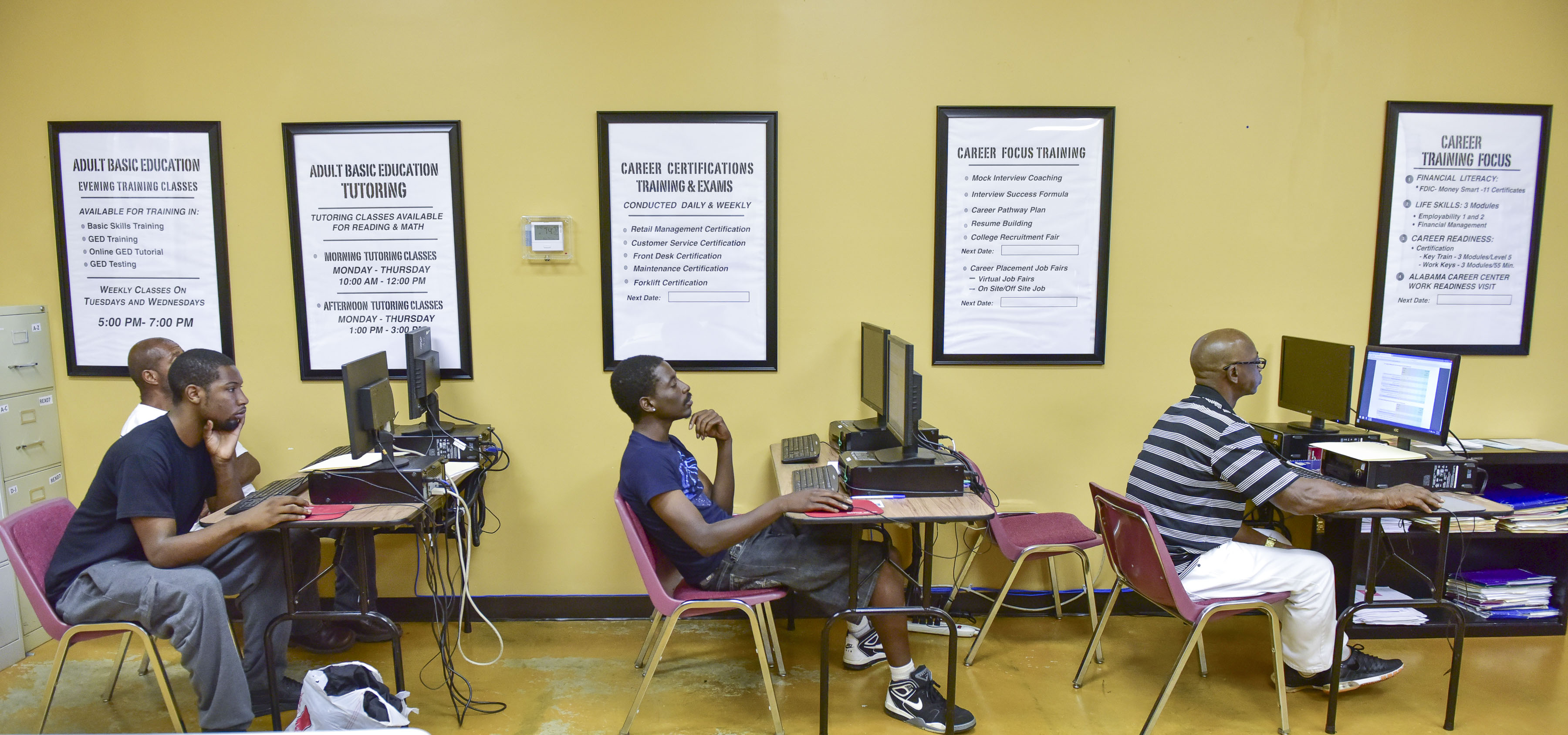

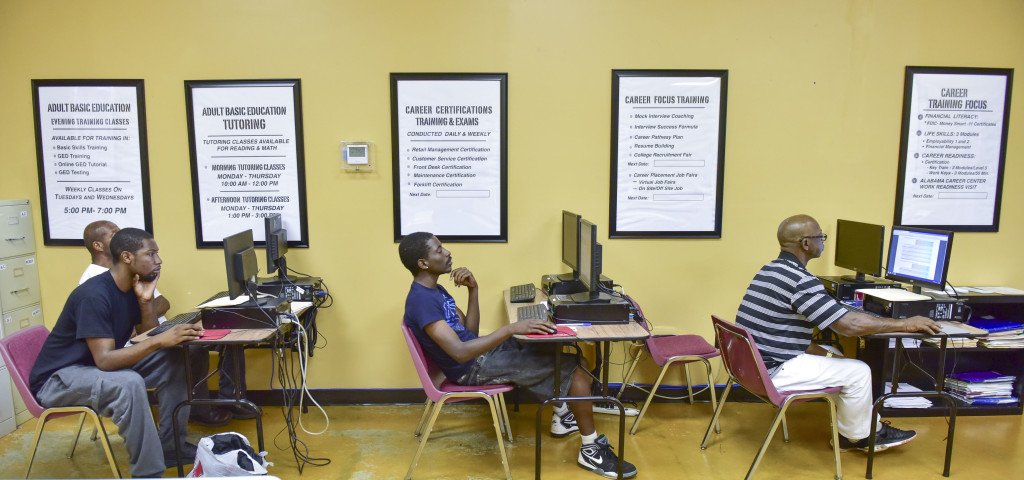

Since coming home three months ago, Whitehead has been on the right road thanks to the Dannon Project, a nonprofit based in Alabama’s Jefferson, Calhoun, and Clarke counties that helps former inmates survive and thrive.

The Dannon Project, which does not serve anyone convicted of violent crimes and rape, has helped change the course of those who return from incarceration. The organization gives them a chance to find their footing in a world where they might otherwise feel discarded.

“Without it, so many guys would go right back to prison,” Whitehead said of the nonprofit. “A lot of people don’t have anything to go back to. There’s nothing for them out here.”

The Dannon Project, founded in 1999 and given nonprofit status in October 2003, serves 600 to 700 people each year and has worked with approximately 8,000 at-risk individuals since it was established. The organization helps people in transition, especially those who have addictions and are on the road to recovery. It supports people who are unemployed or underemployed, as well as at-risk youth and adults, both male and female, and specifically nonviolent offenders reentering society.

Recidivism Rates

The Bureau of Justice Statistics found high rates of recidivism among released U.S. prisoners, and this paints a gloomy picture for those who have served time. One study tracked 404,638 prisoners in 30 states after their release from prison in 2005 and found that within three years of release about two-thirds (67.8 percent) of released prisoners were re-arrested.

That’s where the Dannon Project comes in. According to staffer André Taylor, the recidivism rate for released inmates after they have gone through the organization’s adult re-entry program is 3 percent.

The nonprofit, which also assists at-risk youth in Central Alabama, recently received $5.86 million from the federal government to continue its re-entry and career-pathway programs. It was one of 40 organizations in the nation to receive the grant from the U.S. Labor Department.

“A lot of times when [individuals] come out of prison, they don’t have anywhere to go because their families have turned against them,” said Taylor, who heads the Dannon Project’s Face Forward program. “But we open our doors. We are their family. We don’t care what their situations are. We don’t talk about their past. We just talk about the present and the future.”

Moved to Action

The Dannon Project was founded by Fox 6 television anchor and reporter Jeh Jeh Pruitt and his wife, Kerri Pruitt, who serves as the organization’s executive director. The nonprofit is named for Jeh Jeh’s youngest brother Danon Pruitt (spelled with one “n”), who was killed at age 19 by someone who had been released from prison after serving time for a nonviolent offense.

The Dannon Project’s re-entry program begins with case workers going into prison to work with and provide support to inmates prior to release. That guidance continues after they are released: Participants are given access to meals, health care, counseling, child care, and other services to help them get re-established.

“We go through work-skills and other types of training, and we try to help them find employment,” Taylor said. “We help them re-establish their ID, help them get their Social Security cards. A lot of times, once they get locked up, they lose all of that.

“They might be caught up on drugs. They might be homeless,” he continued. “We try to provide all those resources, all those services to help them out of whatever they’re going through.”

Other programs under the Dannon Project umbrella:

- Face Forward serves out-of-school youth and provides training in the medical industry.

- Youth Build helps high school dropouts get a GED diploma and provides training in construction; some of the participants in this voluntary program have been in the court system.

- Out of School Youth trains high school graduates in several trades, equipping them with the skills to become patient-care technicians, certified nursing assistants, and network cable installers, among other positions.

- Training to Work is a re-entry employment opportunity and adult re-entry program centered on addressing the needs of offenders.

Woni Lawrence knows the benefit of the Dannon Project firsthand. The former accountant served 20 months at Marianna Federal Prison Camp in Marianna, Fla., for embezzlement. She used her bus ticket to get to Birmingham and Keeton Corrections, a federal halfway house where she served six months before moving in with her mother in Roebuck.

“It is very hard to get your life back,” Lawrence said. “For so many, survival is literally a day-to-day struggle (and) prison is a revolving door. They can get out and go right back in because they can’t find their life outside of being incarcerated.”

A person who is incarcerated may lose his or her Social Security card and birth certificate, both of which are needed to get a job. They may lose their right to vote. Without these things, a person can become a virtual noncitizen.

“That’s the way society looks at it, and it shouldn’t be that way,” Taylor said. “We offer a second chance. We try to give them another opportunity to get back into society.”

A Blessing

Kenneth Whitehead thought he would be a pro football player before he dropped out of Wenonah High School. After growing up in church, his life changed course when his grandmother died.

“I turned into another guy,” he said. “I was evolving. I was about 16, selling drugs. I thought I was the big man, keeping some money on the table. Sometimes you make wrong decisions that cost you forever.”

The oldest of five children in a single-parent household, Whitehead said he “had to do something.”

“There was no daddy. There was just momma,” he said. “She couldn’t do it all by herself. I had to do something. [Selling drugs] was the only thing I could do to keep money and keep something to eat. It was helping ends meet.”

After being released from Ventress Correctional Facility on April 4, Whitehead signed up for the Dannon Project when a friend recommended it. Now he has acquired job skills and learned how to conduct business.

“I got my ID, my Social Security card, my birth certificate, all that through the Dannon Project,” he said, adding that he has earned a certified forklift operator license and now works for a produce company.

“They’ve been keeping me going, man, with that extra push, that extra motivation,” Whitehead said of the Dannon Project. “They’ve been like momma and daddy for me since I’ve been out. It’s just a blessing to have something like this for people coming out of prison.”