By Reginald Greene

Special to The Times

I remember so vividly that day back in 2001 when the decision was handed down in Jefferson County Circuit Court, convicting former Ku Klux Klansman Thomas Blanton Jr. of four counts of murder for his role in the fatal 1963 bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church.

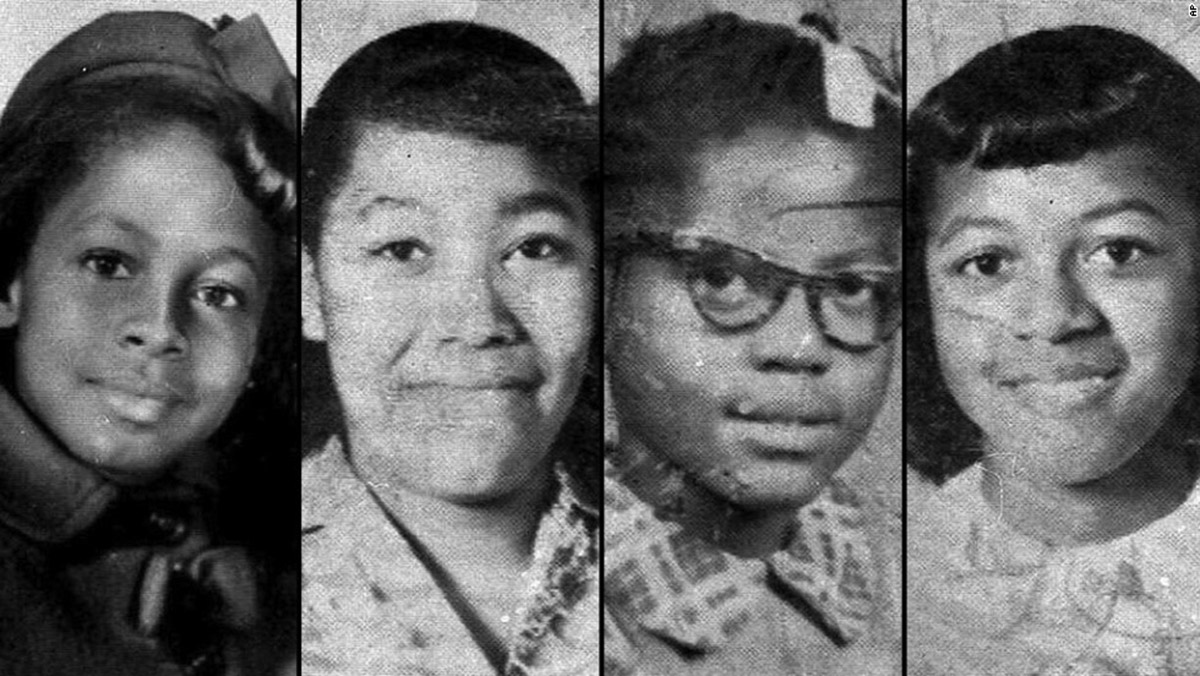

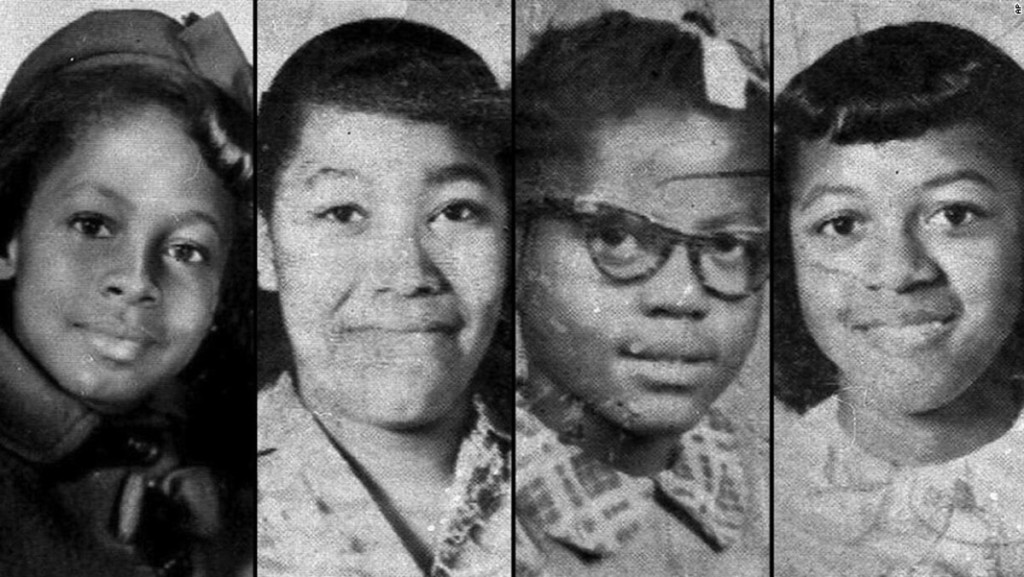

The blast killed four little girls, Addie Mae Collins, Cynthia Wesley, Denise McNair and Carole Robertson.

Covering the story for Cox Radio in Birmingham, I sat in back of the courtroom and watched as Blanton was led away in cuffs by two Jefferson County sheriff’s deputies to begin serving four life prison sentences.

As the crowd filed out of the chamber, I remember glancing over at Mrs. Alpha Robertson, mother of Carole Robertson. The expression on her face showed some semblance of relief and calm that justice had been served after 38 years, but no joy. Joy and peace would never return to Mrs. Robertson or any member of her family, even though three of the four suspects accused in the fatal explosion would be tried and convicted. (“Dynamite” Bob Chambliss in 1977, Blanton in 2001 and Bobby Frank Cherry in 2002. Both Chambliss and Cherry died in prison. Blanton is now 86.)

Now comes news that after serving only 15 years of four life sentences, under Alabama law, Blanton will be considered for possible parole during a hearing scheduled for next Wed. August 3 before the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles in Montgomery.

The families of the bombing victims are outraged.

“My family had to wait for 38 years — almost four full decades — for justice to be served in the case of Thomas Blanton,” wrote Dianne Braddock, Carole’s older sister, in a letter earlier this month to the paroles board. “The least the state of Alabama can do is require him to serve the life sentence he was given.”

Years after Blanton’s trial I married into the family of Carole Robertson. My wife, attorney Gaile P. Gratton, is the first cousin of Carole and the niece of Mrs. Robertson. I’ve had numerous opportunities to spend quality time with this closely knit family. With the family I’ve spent weddings, funerals, graduations, birthdays, family reunions and commemorations honoring Carole and the other three victims.

And I can say without equivocation, from up close and personal observation, that the pain and anguish suffered by the brutal slaying of Carole and the others have never gone away. Even after more than 50 years.

Her father, Alvin Robertson Sr. died of a broken heart. Her older brother, Alvin (Buster) Robertson Jr. remained embittered over the incident for the remainder of life, refusing to grant interviews, even to movie maker Spike Lee during the filming of the documentary “Four Little Girls”.

Last year Carole’s sister Dianne Braddock, her nephew Stephen Robertson and I cleaned out the old house where she was born. We found report cards from Wilkerson Elementary School, a green Girl Scout sash and the clarinet she practiced on in preparation for her first performance with the Parker High School marching band in 1963. She never got to play with the band.

Mrs. Robertson had saved literally dozens of pictures, awards, certificates and anything relating to the short life of her baby girl.

Although Dianne was grateful to have found them, her sadness was palpable. What could possibly erase the horrible image of losing her little sister in such a savage and horrendous way?

According to former U.S. Attorney Doug Jones, who was the lead prosecutor in Blanton’s trial, members of the paroles board must consider whether a prisoner has accepted responsibility for the crimes he was convicted of and whether he has shown any remorse. So far, Blanton has done neither.

“When Thomas Blanton finally was brought to justice, he didn’t have a single word to say to the families of the victims. Not ‘I’m Sorry’ or ‘Please forgive me.’” Braddock wrote in her letter. “Life must mean life — especially when the murderer’s own life has not been taken.”