From Billie Holiday to Marvin Gaye to Beyoncé—What’s Going On

By Ariel Worthy

The Birmingham Times staff

Many in America were shocked.

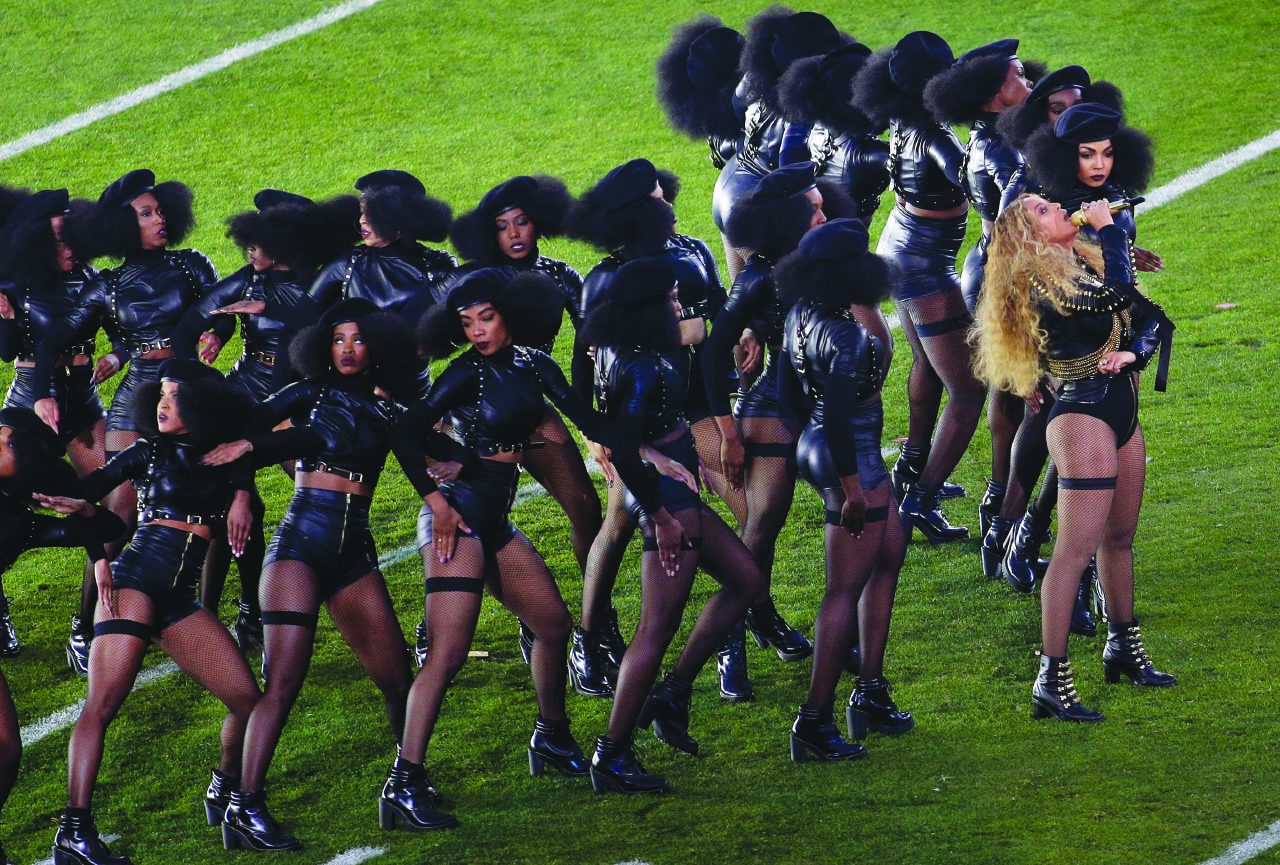

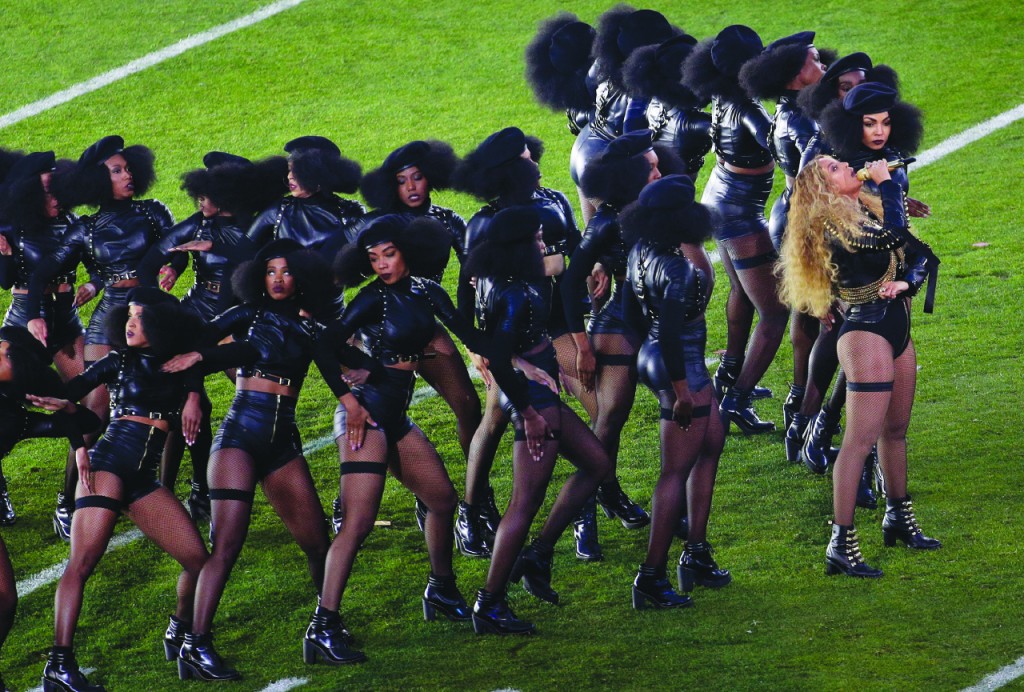

Megastar Beyoncé and her backup dancers donned costumes reminiscent of the Black Panther Party, whose members projected black empowerment—during the Super Bowl halftime show, one of television’s most-watched events. What’s more, the dancers arranged themselves in the shape of an X, possibly paying homage to black nationalist leader Malcolm X.

The video for Beyoncé’s “Formation” is filled with images of Hurricane Katrina and the symbols of the black South. In one scene, a young black boy dances in front of police officers with his hands held up, then the words “Stop shooting us” are shown spray-painted on a brick wall.

Former New York City Mayor Rudy Giuliani called the Super Bowl performance “outrageous,” and Rep. Peter King (R-N.Y.) said in a Facebook post that it was “just one more example of how acceptable it has become to be anti-police.”

Edward Bowser, AL.com community manager and founder of music and pop-culture blog SoulInStereo.com, said the criticism from Giuliani and King did not surprise him.

“Just look at the political climate,” Bowser said. “America has drastically changed over the past decade. For the first time, possibly ever, mainstream America isn’t the topic of conversation. Minority issues are becoming mainstream, and some critics interpret that paradigm shift as an attack on their personal beliefs and values. Instead of joining the discussion, they warp it, suddenly transforming empowering songs like ‘Formation’ into supposed attacks on police.”

If the Beyoncé performance wasn’t upsetting enough to some, a week later rapper Kendrick Lamar emerged shackled, in prison clothes, and surrounded by jail bars—onto the stage during the Grammy’s, often called “music’s biggest night.” He rapped about his facial features and skin in “Blacker the Berry.” His lyrics boldly stated how white people make money by killing and locking up black people.

“I thought Kendrick’s performance was powerful and it needed to be done,” said Bryson Henry, a Birmingham resident who closely follows hip hop. “No one should be surprised. Just look at the concept of his album. It was coming sooner or later and it couldn’t have come at a better time than the Grammys.”

These high-profile events aren’t the first time in music history that protest songs have been extensively criticized or acclaimed.

Social Issues

Marvin Gaye received much acclaim for his 1971 album “What’s Going On.” The album—featuring passionate compositions on war, racial strife, and ecology—revolutionized black music and ushered in a new era of pressing social issues, many of which still make headlines and inspire music.

Whether Bob Marley sings “Get Up and Stand Up” or Public Enemy raps “Fight The Power,” artists continue to take a stance on issues of the day through their art.

“Songs like ‘What’s Going On’ and ‘Fight the Power’ had a broad sense of what was happening,” said Ronald Grant, an Atlanta resident, who is a hip hop scribe. “Marvin Gaye talked about Vietnam, he talked about the environment and he talked about inner-city situations.”

Grant said those broad themes are in contrast to some today’s protest songs which have a more specific message such as Macklemore’s “Same Love” which speaks on same sex marriage.

Of course, protest songs predate Gaye’s momentous album. Billie Holiday sang and recorded “Strange Fruit,” a song that protested the lynchings of black men in the 1930s. James Brown chanted “Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud,” which became an unofficial Black Power anthem during the turbulent 1960s.

Protest songs also are not limited to the black experience.

Bob Dylan and Bruce Springsteen are known for socially conscious songs that still carry weight. In 1964, Dylan wrote that “The Times They Are A Changin,” a tune that still resonates among blacks and whites alike. And in 2001, Bruce Springsteen wrote “American Skin (41 Shots)” about an unarmed black man being shot 41 times by New York City police officers.

Following in Their Footsteps

During this month’s back-to-back performances, Beyoncé and Kendrick Lamar, following the lead of their forebears, brought protest music into the public discourse and aroused both criticism and praise.

Law-enforcement officials across the country are offended about Beyoncé’s performance. The New York Police Department has demanded an apology. And according to a CNN.com report, “support for a national law enforcement boycott of Beyoncé’s world tour appears to be picking up steam,” with organizations like the National Sheriffs’ Association and the National Association of Police Organizations voicing their displeasure.

Still, many believe the singer’s message was on-point.

“The messages presented by Beyoncé and Kendrick rang loud and clear: blackness is no longer niche,” Bowser said. “It’s mainstream. It’s part of American culture, and it should be celebrated.”

Bowser added, “Beyoncé’s performance celebrated her Southern roots, her daughter’s kinky hair, and her husband’s black facial features, all of which are typically looked down upon or criticized in mainstream media. Her messages to both black America and mainstream audiences were the same—love yourselves and love us.

“Kendrick’s spirited performance, during which he literally tossed aside his shackles and saluted Africa, simply echoed those sentiments. In 2016, black issues are American issues. That message was broadcast to the world,” Bowser said.

‘Don’t Shoot’

What was behind the performances, though? Were they done for commercial or social reasons?

Beyoncé’s “Formation” video, which is nearly five minutes long and has been viewed more than 22 million times on YouTube, shows the words “Stop shooting us” after a little black boy dances in front of a line of police officers. This is a direct reference to Black Lives Matter movement marchers who often held up their hands and chanted “Hands up, don’t shoot,” which was allegedly the stance taken by 18-year-old Michael Brown before he was gunned down by police officer Darren Wilson in the summer of 2014 in Ferguson, Mo.

“Artists like Common and Lupe Fiasco have built careers around these messages,” Bowser said. “Lupe Fiasco, in fact, released an album two months before Kendrick Lamar’s heralded ‘To Pimp a Butterfly’ that was equally filled with powerful songs.”

But even Bowser acknowledged that Beyoncé’s performance may have caught some off-guard.

“While Lupe Fiasco, Kendrick Lamar, and others have long been seen as niche conscious rappers, Beyoncé is a beloved pop star with worldwide acclaim,” Bowser said. “I’d like to think that she’s decided to speak out because now, more than ever, black voices are at their loudest and opposition against them is becoming more fervent.

“Beyoncé is using her incredible platform to add credibility to those voices and, more importantly, make these issues mainstream. Bey simply realizes her power and is deciding to join the conversation. I’m happy to have her on board,” said Bowser, who often addresses on controversial social issues in his column.

Times staff writer Barnett Wright contributed to this article.