by Ariel Worthy

With so much race debate in the country, there is one topic that sometimes gets overlooked: how Black children are disciplined compared to white children in school.

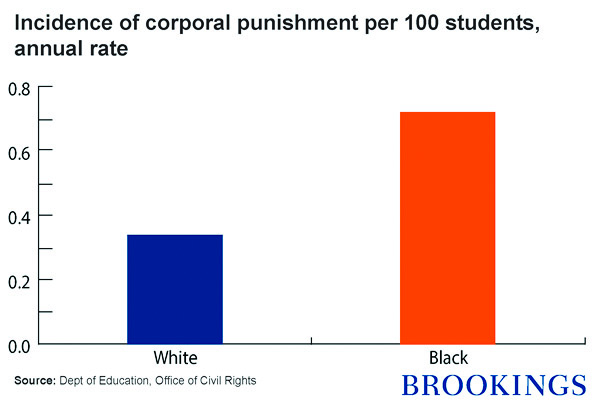

In public schools in the U.S., Black children are twice as likely to be subject to corporal punishment compared to white children.

There have been 42,000 reported incidents of Black boys being beaten, and 15,000 incidents for Black girls, by educators in their schools. These reports indicate two facts: Black students are more likely to be located in states that use corporal punishment extensively; also, in many states Black students are disproportionately likely to be singled out for corporal punishment.

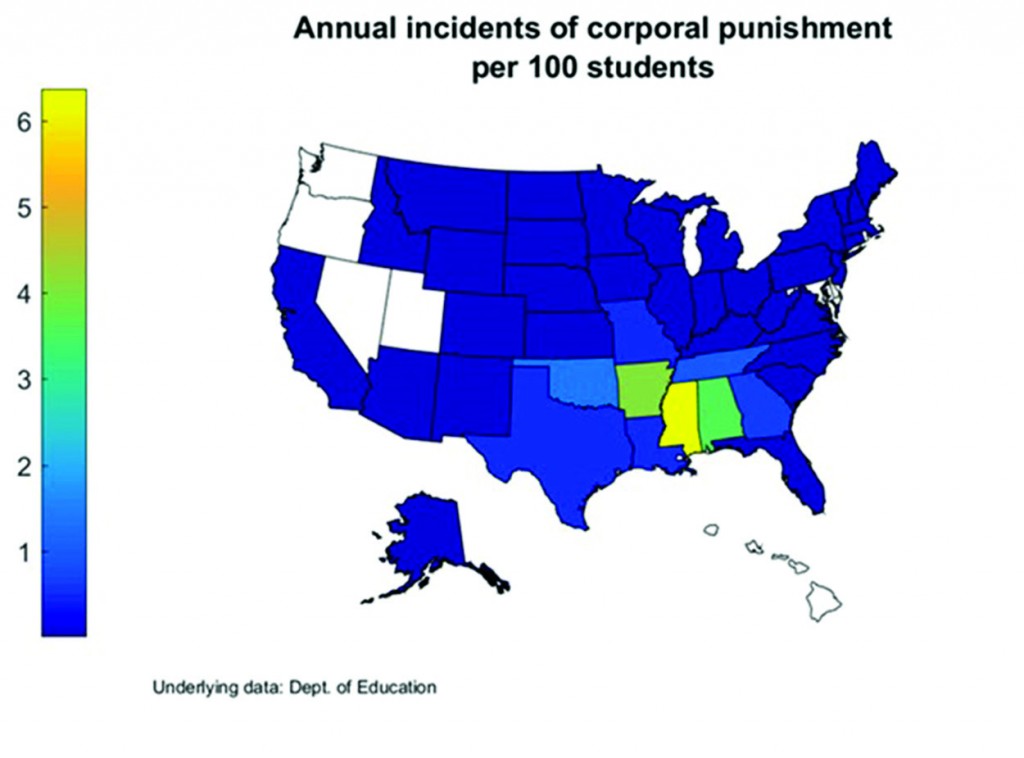

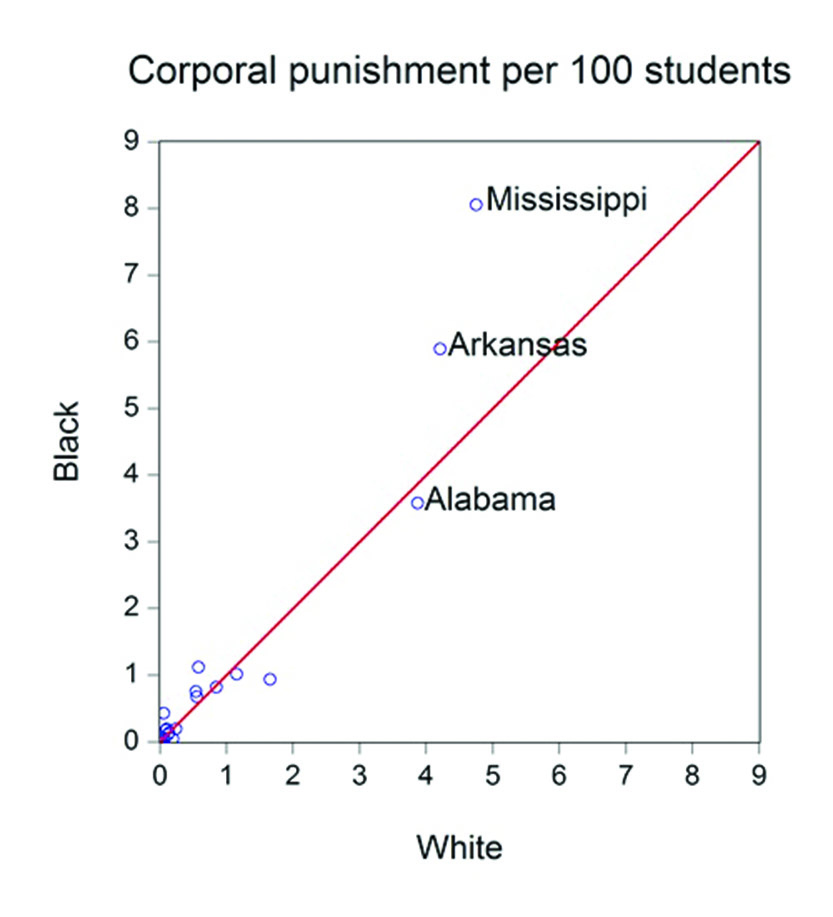

While corporal punishment is used in almost every state, seven states account for 80 percent of school corporal punishment in the U.S.: Mississippi, Texas, Alabama, Arkansas, Georgia, Tennessee, and Oklahoma. For Black students, six of those states – Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Arkansas, Texas and Tennessee – as well as Louisiana account for 90 percent of corporal punishment. One reason that Black students are subject to more corporal punishment is that they live in those states responsible for most of the corporal punishment of all children.

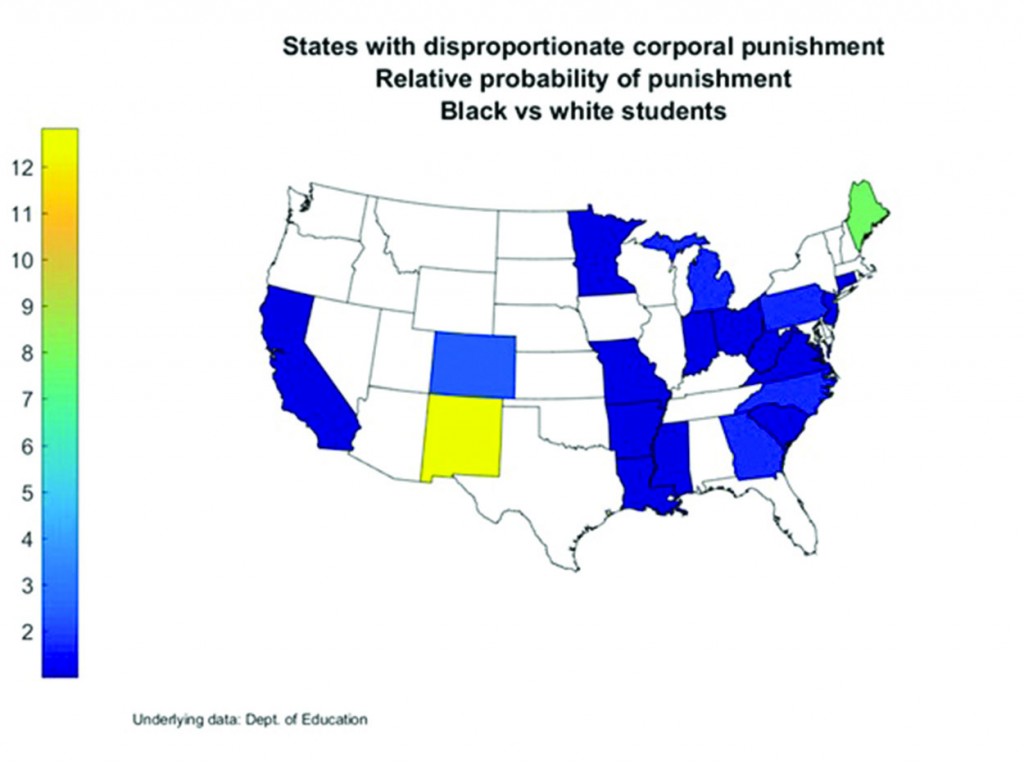

So where does this show that corporal punishment is disproportionate? Sadly (and somewhat unsurprisingly), right here in the Deep South. Black students are twice as likely to be struck as white students in North Carolina and Georgia, 70 percent more likely in Mississippi, 40 more likely in Louisiana, and 40 percent more likely in Arkansas.

Some high corporal punishment states are not racially disproportionate. Texas, notably, uses corporal punishment on Black students and white students with equal likelihood. Texas shows up on the lists of where Black students are hit because it is a large state that administers corporal punishment at a moderately high rate.

Here in Alabama the rate of corporal punishment is 10 times the national average. It does, however, show equal rates of Black and white children experiencing physical violence from educators.

In North Carolina, Black students are twice as likely to be struck as white students, but North Carolina uses corporal punishment infrequently and so accounts for a small proportion of punishment of Black students. In South Carolina the rate of corporal punishment is below the national average and is not racially disproportionate.

While the Confederate states use corporal punishment more frequently, racially disproportionate application happens in northern states as well. Schools in Pennsylvania and Michigan are nearly twice as likely to beat Black children as white children, although both have low overall rates of corporal punishment.

Surprisingly, Maine is significantly disproportionate – with Black children being eight times as likely to be hurt as white children. Colorado, Ohio and California also have rates over corporal punishment for Black children that are 70 percent or more higher than for white children.

While the symbolism of continued physical violence against Black children is inescapable, the disproportionate application of other forms of discipline may be of even greater concern. Except in Mississippi and Arkansas, the typical Black student will probably not be subjected to corporal punishment during his school career.

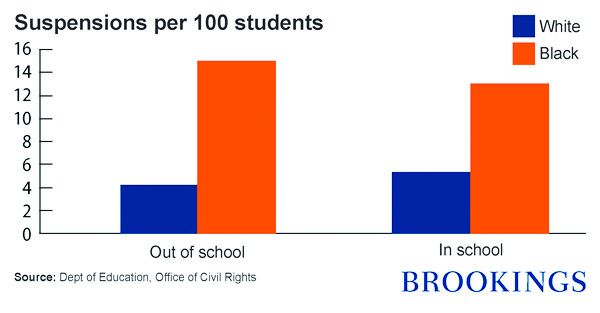

In contrast, school suspensions are much more common.

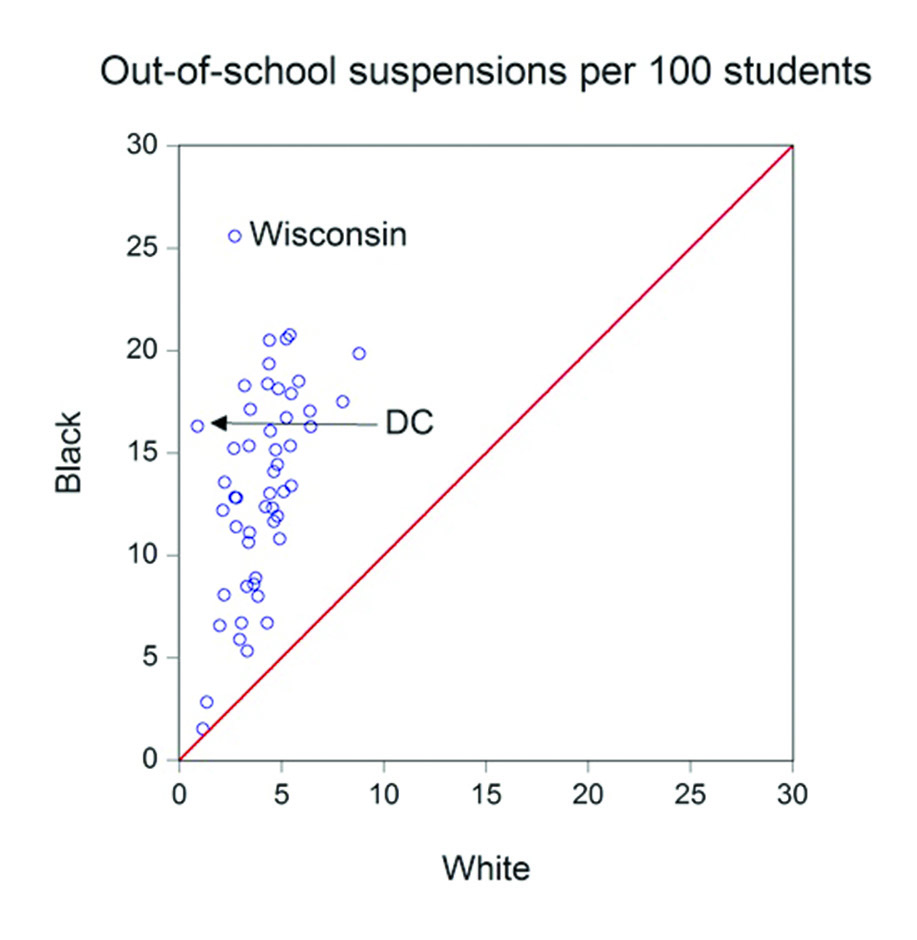

Out-of-school suspensions are applied disproportionately in every state – all points are above the red line. And these discipline patterns do not line up with old geographic patterns. The highest suspension rates for Black students are in Wisconsin. And the greatest disparities (measured as the ratio of Black-to-white suspension rates) are in Washington D.C.

Every time a child is beaten in school and every time one is suspended and thus loses learning time, something or someone has failed that child along the way, regardless of the “reason” for the punishment. So long as these failures fall disproportionately on Black children, we are not yet living up to the dream that “children will one day live in a nation where they will not be judged by the color of their skin but by the content of their character.”

(All data is for the 2011-2012 school year, the latest year available.)

(Charts and information found on Brookings.edu.)