Johnnetta Cole and the Bill Cosby Merry-Go-Round

By

James Strong

Here we go again. First, it was Whoopi Goldberg and her support of Bill Cosby. Then, it was R&B singer Jill Scott and her indefensible defense of that accused serial rapist.

Now, we have Johnnetta Cole, the black director of the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art, who has moved her support for Bill Cosby to the forefront of the public’s attention by hiding it in the farce of a false argument suited for fairies and fairy tales.

The Root, a black news website co-founded by Henry Louis Gates, Jr., Director of the Hutchins Center for African and African American Research at Harvard University, published an article by Cole titled “Why I Kept Open an Exhibit Featuring Art Owned by Bill Cosby.”

Cole, in case you did not know it, and because The Root wants you to know it, “is president emerita of Spelman College and Bennett College for Women and has been awarded 68 honorary degrees. In 2015, BET awarded her its BET Honors award for education.” Wow, how impressive!

Cole has endured nearly endless criticism from women’s groups, opponents of rape and those raped by Cosby for her decision to retain art work donated by Cosby and his wife Camille in the “Conversations” exhibit of African and African-American art at the Smithsonian. And the Smithsonian has taken heat for yielding, like a slave, to the whim of a female black intellectual respected in both black and white academia.

Cole’s decision to keep the exhibit open rests on one central premise: “Art must be allowed to speak for itself.” And from this premise she asserts “that this exhibition is not about the life and career of Bill Cosby. It is about the interplay of artistic creativity in remarkable works of African and African-American art and what visitors can learn from the stories this art tells.”

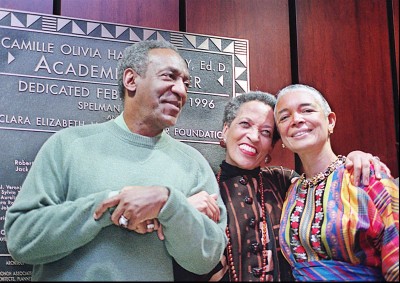

What intrigues us about Cole’s article is that for some reason in the first paragraph, she spends time in celebrity worship, worshiping Bill and Camille Cosby and her professional and personal relationship with them, celebrating the Cosby’s $20 million donation to Bennett College, and fawning in a manner reminiscent of stray cats meowing for food over Camille Cosby’s membership on the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art’s board of advisors.

I guess it never dawned on Cole that she admitted to a conflict of interest in her decision—a decision that was not objective, a decision demeaned by her close and personal relationship with the Cosbys, a decision where money and celebrity idol worship are more important than integrity, a decision about as fireproof as a gallon of oil.

But the more serious error in Cole’s thinking emerges from her art for art sake’s premise, a theory based on a traditional European aesthetic that Amiri Baraka and other influential black figures in the black aesthetics movement fought so hard to combat.

That European form of aesthetics says that art is divorced from its creator, such that it does not matter whether the writer or painter or photographer is a Hitler, a slave owner, a mass murderer or a rapist, and that we can still showcase his artwork, whether or not the artist suffers from his lifelong past time of crime and terror.

In contrast, the black aesthetics movement taught us that art and the person who created or donated the art are one, that they are not separate from each other but an expression of each other, and that art expresses not only universal ideas, but personal, social, political, racial and cultural ideas as well. Thus, if the artist is a rapist, his art represents him as both artist and rapist, as both artistic creator and sadistic animal.

Besides, the reasoning underlying the black aesthetics corresponds to practices of law that undergird the existence of lawsuits and the prevalence of circumstantial evidence in criminal cases. U.S. civil laws permit the victims of a crime to sue the perpetrators of a crime to gain the assets owned by the perpetrators as compensation for emotional and other distress, whether or not the perpetrators are convicted of their crimes and even though the perpetrators and their assets are separate and distinguishable.

Prosecutors use circumstantial evidence to prosecute persons accused of a crime, even if there is no direct evidence linking that person to the crime and even though the circumstantial evidence may have little indirect link to the accused or the crime supposedly committed by the accused.

In this sense, the art work owned and donated to the Smithsonian by Cosby is an extension and expression of Cosby—his personality, his character and his escapade as a serial rapist. And if this argument is reasonable, if the oneness principle, this unity of person and the person’s associations, so heavily relied upon in law is applicable, much more should it apply in the Cosby Smithsonian case. Because the powerful issue of moral accountability is also at stake, not only for Cosby, but also for Cole and the Smithsonian.

In fact, it does apply, as Judy Huth, who claimed that Cosby sexually assaulted her at the Playboy Mansion when she was just 15-years-old, filed a lawsuit against him, and may be able to seize his assets, including any other art work Cosby owns, if she wins her suit.

And with that possibility in mind, “art must be allowed to speak for itself” does indeed speak for itself, because Cole admits that the Cosbys donated “$716,000 to assist with the cost of this exhibition.” But the art work donated by the Cosbys complains that “I was duped. I was not given to the Smithsonian merely as a gift, but also as a bribe. And I am an unwilling participant in this bribe.”

Could be that in hindsight Cosby donated the art work in foresight, in anticipation that the day would come when he would be either indicted for rape, convicted of rape or sued for rape, and that he needed someone (or an organization) who would willingly and morally submit to his bribe?

If this contention is reasonable, then Cole’s claim—that “When we accepted the gift and loan, I was unaware of the allegations about Bill Cosby. Had I known, I would not have moved forward with this particular exhibition.”—lacks both reason and believability.

How could a woman with 68 honorary degrees not know about rape accusations against Cosby, which have been revealed in major media from The New York Times to the Washington Post, from NBC News to CNN, for more than 20 years?

And how come she would have postponed the exhibit if she had known about the rape allegations against Cosby before the exhibit began, yet is unwilling to at least remove Cosby’s part of the exhibit when she found out about the allegations after the exhibit began?

Moreover, Cole’s attempt to link Cosby’s art work with the “Conversations” exhibit is as deceiving as the image in a mirror. It is so dishonest and reminds us of a shrimp boat captain ordering his reluctant sailors to dive for shrimp in shark-infested waters by assuring them that the sharks are too docile to bite and eat them.

Hardly anyone wants Cole and the Smithsonian to close the exhibit; mostly everyone asks that they remove Cosby’s donated art from the exhibit. Because the art work insults the women raped by Cosby and shows that Cole and the Smithsonian shamefully exploit the women and their ordeal, without any sense of morality, without any notion of integrity, for money and profit, merely because Cosby is a friend, a celebrity and a serial rapist.

And if Cole and the Smithsonian are not brave enough to do the right thing, if death is only a temporary sleep, then we hope the hundreds of millions of women raped and defiled over 200,000 years of human history rise from their graves and spit the semen of their rapists in the faces of Cole and the Smithsonian.

Copyright © 2015 by James Strong. All rights reserved. Reproduction or translation of this column, or any part of this column, without permission of the copyright owner is unlawful. Send your comments to strongpoints123@gmail.com.