From Staff Reports

Forty-nine years after John Lewis and other marchers tried to cross the Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Alabama, memories of “Bloody Sunday” are still vivid in his mind. It was one of the defining moments of the civil rights era.

“We were beaten, tear gassed, trampled and chased by men on horseback,” said Lewis, a civil rights activist and Democratic congressman from Georgia.

Lewis — portrayed by the actor Stephan James in the historical drama “Selma” — told The Associated Press the film is “very powerful.”

“Selma,” directed by Ava DuVernay, is based on the 1965 marches in Alabama led by the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Lewis says the film’s release now is fitting after protests over events in Ferguson, Missouri, and elsewhere.

According to ˆThe Detroit News”, As the movie “Selma” goes into wider release this week, veteran Detroiters will be reminded of a link our city has to the violent events of March 1965 in Selma, Alabama.

Viola Gregg Liuzzo, 39, a Detroit mother of five, was one of three people killed in Selma during voting rights demonstrations. Liuzzo was shot and killed March 25, 1965, by Ku Klux Klansmen on a desolate stretch of U.S. 80 as she drove Leroy Moton, a Black demonstrator, back to Montgomery.

“Selma,” tells the story of those violent weeks when the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. helped lead a push for federal action protecting Black voting rights in one of the most racist counties in Alabama.

Liuzzo’s daughter, Mary Liuzzo Lilleboe, was disappointed at first when she heard that her mother’s story isn’t highlighted in the film. “You become hypersensitive to the details, you want everything to be perfect about your loved one, but it’s never going to be that,” said Lilleboe, 66, an Oregon resident.

Marchers including the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. and wife Coretta, center, during the five day, 50 mile march for voting rights from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, March 1965. (Photo: The Detroit News archives)

Her mother would have told her to keep her eye on the big picture.

“My mother would not have been concerned about credit or somebody knowing that she was even part of it,” Lillieboe said. “What she cared about was that people were being helped.”

And because of “Selma,” younger generations will find out what went on there. Lilleboe is also pleased that King is the lead character in a feature film, for the first time ever. “Can you believe that?” she said.

Lilleboe’s sister, Sally Liuzzo, lives in Tennessee and runs a Facebook page, “Viola Liuzzo Civil Rights Martyr,” in tribute to their mother. In just a week after the movie’s initial release and the airing of an Oprah Winfrey “Selma” special Sunday, it added 180 new likes, and the number rises every day.

Before Liuzzo was murdered, two others were killed in or near Selma: Jimmie Lee Jackson, a Black civil rights worker shot by state troopers, and James Reeb, a white Unitarian minister beaten to death March 11 after leaving a restaurant.

Their murders are shown in the film; Liuzzo’s is not. Liuzzo is portrayed in the film by actress Tara Ochs, and she is first seen sitting with her husband in a modest living room, recoiling in horror at the images on TV of Selma marchers being beaten and tear-gassed on “Bloody Sunday.”

Ochs isn’t identified at first as Liuzzo, but she gets a lot of face time in the film. She’s also seen helping volunteers, and then marching along U.S. 80. At the end of the film, there is text under her image identifying her as Viola Liuzzo, murdered by the KKK as she drove a demonstrator home.

Although she has no lines in “Selma,” Ochs is a magnetic presence as Liuzzo.

“I have no doubt that the very simple but powerful way that (director) Ava (DuVernay) included Viola in the story will be the catalyst for many people finally recognizing and appreciating this incredible woman,” Ochs wrote The News in an email. “It speaks volumes that the struggle for civil rights was felt in Detroit as well at that time, and not just in the South. That’s a powerful message for today, don’t you think? Sometimes we Southerners feel that this struggle is all our fault, and all our fight. But as Mrs. Liuzzo said: ‘It’s everybody’s fight.’ ”

Ochs will meet with Liuzzo’s adult children in Selma in March, at a 50th anniversary commemoration.

When the events at Selma started, Liuzzo was a student at Wayne State, where she was studying sociology. The thrice-married Detroiter was feisty and outspoken. She was always picking up stray animals and pointing out injustice to her five children, Sally, 6; Tony, 10; Tommy, 14; Mary 17, and Penny, 18.

She was born in Pennsylvania, but grew up in Tennessee, where she saw the effect of Jim Crow laws firsthand, before moving to Detroit. “How would you feel if you never saw a white Santa Claus or a pretty white girl on a magazine cover?” she would ask her children.

Some vestiges of her Southern background that remained were her cooking, and the fact that she liked to go barefoot — Liuzzo shucked her shoes in the Selma march.

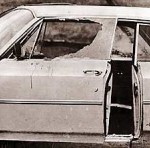

She loved classical music, and studying with friends at the family house on Marlowe in northwest Detroit. When she heard about her friends’ plans to go to Selma after King’s call for action, she told husband Anthony that she hoped he’d understand, and left March 16 in her 1963 Oldsmobile.

After her murder, Anthony, a business agent for Teamsters Local 247, spoke to The Detroit News about his wife. King called three times that day, the president four times, as the shattered family absorbed the shock.

“She was a champion of the underdog,” Liuzzo said. “She thought people’s rights were being violated in Selma and she had to do something about it in her own way. That was her downfall. Many times I had told her, ‘One of these days, the humanitarian things you do are going to backfire. And she would answer, ‘Man is man no matter who or what he is.’ ”

Oldest daughter, Penny Liuzzo, then 18, said: “Mother felt there was too much talk and not enough action, and she wanted to do something.”

Liuzzo and her Wayne State friends weren’t the only Michiganians who went to Selma. A delegation of 22 Metro Detroit religious leaders left for the embattled Southern city, including Protestant, Catholic, Jewish and Eastern Orthodox leaders. U.S. Reps. John Conyers and Charles Diggs flew down from Washington, D.C.

Downtown Detroit was the site of a sympathy march March 9, led by Gov. George Romney and Detroit Mayor Jerome P. Cavanagh that drew more than 4,000, including Rosa Parks.

The news of Liuzzo’s death was front-page news in Detroit. Teamsters president James R. Hoffa had her body flown back to Detroit, and Teamsters guarded the Liuzzo home around the clock, as their wives cooked and cleaned.

The years after Liuzzo’s death were difficult for her family. Her children were harassed at school in Detroit, and a cross was burned on the family’s lawn. There was a smear campaign against Liuzzo, with charges that she had gone south to consort with other men, stories that were eventually traced to FBI director J. Edgar Hoover.

Soon after Liuzzo’s murder, director Hoover admitted that an FBI informant, Gary Thomas Rowe, was among the Klansmen in the car who shot and killed her. Rowe identified the three other Klansmen to authorities, but they were acquitted of Liuzzo’s murder. (Rowe was granted immunity).

The Klansmen were convicted of violating her civil rights in a federal trial. Rowe disappeared into the witness protection program, and died in 1998. A lawsuit the Liuzzo family brought against the FBI and Rowe for his role in Liuzzo’s murder was dismissed in 1983 by U.S. District Judge Charles Joiner.

Was her sacrifice worth it? For Americans already sickened by the civil rights violence, the death of two white northerners gave what had been happening to generations of Blacks a visceral impact. The passage of the Voting Rights Act, a long shot previously, gained momentum. President Lyndon Johnson signed the bill into law in August.

Lilleboe believes it was worth it, even to her grieving family.

“I think all of us would say that our lives have been really rich, we’ve gotten a lot by being my mother’s children,” said Lilleboe. “One of the most damaging things that people said to us was that our mother didn’t love us, or she wouldn’t have gone down there. But the love I have received from people because I am my mother’s daughter, that’s helped, because it was absolutely the way I experienced my mother’s love.”

swhitall@detroitnews.com

A Selma timeline

Feb. 26, 1965: Jimmie Lee Jackson is killed by an Alabama state trooper in a cafe, after he took part in a voting rights march in Marion, Alabama, near Selma.

March 7: “Bloody Sunday,” the march from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama, organized by the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., but led by others in his absence. State troopers attacked the marchers on the Edmund Pettus Bridge. The violent images disturbed many, including President Lyndon B. Johnson.

March 9: King resolves to try to march again, and does, although he has been forbidden to by a federal judge. After state troopers step aside for the marchers, King decides it could be a trap, and turns back to Selma.

March 11: Boston minister James Reeb, who had traveled to Selma to take part in the voting rights marches, dies after being clubbed on the head by an attacker. He had been set upon by white supremacists after leaving a restaurant.

March 15: Johnson introduces a bill to Congress that would become known as the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

March 25: Detroiter Viola Liuzzo is gunned down by Ku Klux Klansmen in her car on U.S. 80, just hours after taking part in the march on Montgomery from Selma. She is driving a Black demonstrator, Leroy Moton, home.

Aug. 6: The Voting Rights Act of 1965 is signed into law by Johnson.