Celebrating Black History

By Alice Bernstein

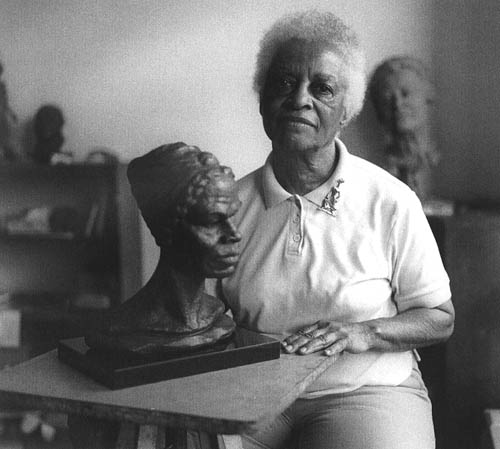

Inge Hardison, the American sculptor, actress, and photographer celebrated her 100th birthday on February 3, 2014. Her life and work embrace much of African American history, past and present-day, and her contributions to the arts have an energy that is big, thoughtful, and stirring. She is best known for a series of bronze busts, begun in 1963, of African American men and women who courageously fought slavery and led the struggle for civil rights, and who at that time had not yet been acknowledged in the National Hall of Fame in D.C.: Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, Harriet Tubman, Dr. Martin Luther King. One sees palpably in her work her great respect for those who helped change history, as in her series, Ingenious Americans, which includes Benjamin Banneker (1731-1806) surveyor, clock-maker, mathematician; and Garrett Morgan (1877-1963), inventor of early traffic lights and gas masks, both of which inventions saved countless lives. She also sculpted large public works: a life-size bronze, Mother and Child (her gift to Mt. Sinai Hospital in Manhattan after the birth of her daughter), and abstract figures such as “Jubilee” at Medgar Evers College in Brooklyn.

As I considered how to be fair to her long, productive life in a brief article now – followed by a fuller one soon – I thought of these sentences from “Aesthetic Realism and Expression,” a lecture by the great philosopher Eli Siegel:

Whenever we do something, we show what we are and also what we want…. [I]n the same way as it is necessary sometimes to stir things to do a better job of cooking, so it is necessary to have ourselves stirred–because we have to be impressed before we can express ourselves.

As one learns of Ms. Hardison’s life, one sees her desire to express herself, variously, energetically, and also to be affected deeply. Wherever she went, she wanted to give form to an aspect of history which stirred her greatly, notably the suffering and achievements of African Americans. She was born in Virginia in 1914, and soon after, her parents fled Jim Crow racism and segregation, settling in Brooklyn. After graduating from high school, she landed the role of Topsy the slave child in the 1936 Broadway production of “Sweet River,” George Abbott’s adaptation of Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Her portrayal of the slave girl whose brutal treatment doesn’t kill the deep kindness in her, won her rave reviews. She played again on Broadway including in “The Country Wife” with Ruth Gordon, and in the 1946 production of “Anna Lucasta,” co-starring with Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee.

In the midst of all this, Inge Hardison discovered clay and was swept by the beauty and power of this substance coming from the earth, and with it her own ability and passion to express herself in this art form. It changed her life. While performing in another play, “What a Life,” she sculpted the heads of the cast members, and the works were exhibited in the Mansfield Theater lobby. In 1942 she attended Vassar, majoring in music and creative writing. There she also gave a song recital and her lyric soprano voice and expressive power was highly praised.

As I must conclude for now, I’d like to mention that I interviewed Inge Hardison last year, while doing research for my oral history project, “The Force of Ethics in Civil Rights” — videotaped interviews with unsung pioneers across the country. The research centered on the very little known history of how Jewish Refugee Scholars, attempting to flee the Nazi Holocaust in the 1930s-40s, were saved by Black colleges in the South who offered them, jobs and safe haven – to the benefit of all. Hampton Institute in Virginia hired one of these refugee scholars, Viktor Lowenfeld from 1939-46. He established the art department and urged his students – among whom was Inge Hardison – to “let expression spring from your environment.”

And so opened a new chapter in the relation of impression and expression in the life of one important, productive, American artist, whose life I look forward to learning about further and having more known.

Alice Bernstein is a journalist, historian, and Aesthetic Realism Associate. “The Force of Ethics in Civil Rights” oral history is a project of the not-for-profit Alliance of Ethics & Art. To learn more: calll (212) 691-2978 or visit online: www.AllianceOfEthicsAndArt.org.