By Barnett Wright

The Birmingham Times

A phone rings inside the Sixteenth Street Baptist Church in downtown Birmingham, Alabama. Fifteen-year-old Carolyn Maull lifts up the receiver.

The date: Sept. 15, 1963.

Maull answers and hears someone on the other end simply say, “Two minutes.”

“They said that, and then ‘click.’ I was just standing there and kind of thought about it, hung the phone up, and stepped out into the sanctuary because I had three or four more classes that I needed to give these cards to,” Maull recalls.

A secretary at the Sixteenth Street Church, Maull is responsible for handing parishioners attendance cards and envelopes to record contributions. “Two minutes,” she remembers the caller saying before hanging up. It is about 10:21 a.m. The temperature outside is forecast to reach a high of 75 degrees on the partly cloudy day.

Sunday school classes are just wrapping up. At the rear of the church in a basement corner lounge, a number of young girls are changing into their choir robes. Just a wall away, hidden beneath the back steps, are 10 to 15 sticks of dynamite. The dynamite explodes, blasting a gaping hole in the stone-and-brick east wall of the church restroom.

Maull recounts the dreadful event that followed: “As soon as I stepped out into the sanctuary—it wasn’t two minutes, it was probably more like five seconds-something happened at that time. I didn’t know the church had been bombed. What I heard at first sounded like a rumble, like thunder. I remember thinking rain-it immediately came to my mind. As soon as I thought rain, all of the windows started shattering, glass came pouring in.

“When that happened, I heard screams all upstairs, screams. Then somebody said, ‘Get on the floor!’ We all got on the floor and were very quiet for what seems like several minutes, but it was probably only twenty or thirty seconds. Then we heard footsteps at that point. Somebody had gotten up and started running.”

Following the detonation is a shower of bricks, stone, and steel that devastates the church lounge, shatters the sanctuary’s stained-glass windows, and hurls large chunks of stone into automobiles and nearby buildings. It rips the clothes off the girls, killing four, decapitating one of them.

Firemen emerge with four battered bodies: Cynthia Wesley, 14, Denise McNair, 11; Carole Robertson, 14; and Addie Mae Collins, 14.

Concerned parents either find their children at the church or hurry to hospitals to search there. The Sixteenth Street Baptist Church bombing and the resulting deaths of those four innocent little girls rip apart the psyche of Birmingham, an already fragile municipality that some say is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States at the time, with more unsolved bombings of Black homes and churches than any other city in the nation.

60th Year Commemoration

Sixteenth Street Baptist Church will observe the 60th year commemoration of the bombing on September 15 at 9:30 a.m. with Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, the first Black women on the Supreme Court of the United States, as the memorial service speaker.

“There have been many events throughout the year to commemorate the Civil Rights Movement in Birmingham. However, on this particular day, we, as a church, will honor the lives of four little girls who lost their lives here, 60 years ago,” said Rev. Arthur Price, pastor of the church. “Because of this act of terrorism on our soil, the world began to take more careful notice of the racial unrest in the South and we look back at that time with reflection and hope for the future.

“We are a different Birmingham, a changing Birmingham, and we are looking forward to forging justice for a better world. We are still standing to tell God’s message of love and redemption and we will never forget [the four little girls killed in the bombing] Cynthia Morris Wesley, Carole Robertson, Denise McNair and Addie Mae Collins,” said Price.

The commemoration is part of a year-long remembrance in Birmingham with the theme “Forging Justice” that includes hosting an international peace conference to a children’s march reenactment, creating a free poster series, and opening of the historic A.G. Gaston Motel.

Mayor Randall Woodfin said, “In the aftermath of that fateful day on Sept. 15, 1963, our city and our nation had to take a hard look at itself and reckon with the devasting effects of hate and racism. Today, in the spirit of the Four Little Girls, we work to be better and honor them by preserving our history and building a future worthy of their sacrifice.”

Well-Known Place Of Worship

Sixteenth Street Baptist Church was the first Black church to organize in Birmingham in 1873. Throughout its history, many prominent Blacks in the city were members and many dignitaries spoke at the well-known place of worship. In the 1960s, Sixteenth Street served as a center of activity for the growing movement against racism in Birmingham and across the South.

Because of that, it became a target.

At the time of the explosion on Sunday, September 15, about 200 parishioners were in the building, recalled Sunday school teacher Effie J. McCaw, who was in the church at the time of the blast. Debris came crashing down in the rear of the church, she recalled, and several people were cut and bruised.

Giant stained-glass windows—18 feet wide by 23 feet tall—were shattered. One of the windows depicted Jesus Christ leading a group of children. After the blast, Christ’s head was blown away; his body remained. A skylight fell directly on the pulpit. Stairs leading from the sanctuary to the basement were splintered. The banister, turned loose, looked like a picket fence.

A huge crater was dug by the blast at the 16th Street entrance. The concrete steps that led to the main-floor sanctuary from the side door were blown away. A police detective said the bomb had been placed in a rarely used stairwell outside the restroom. Members of the Ku Klux Klan were immediately suspected in the bombing.

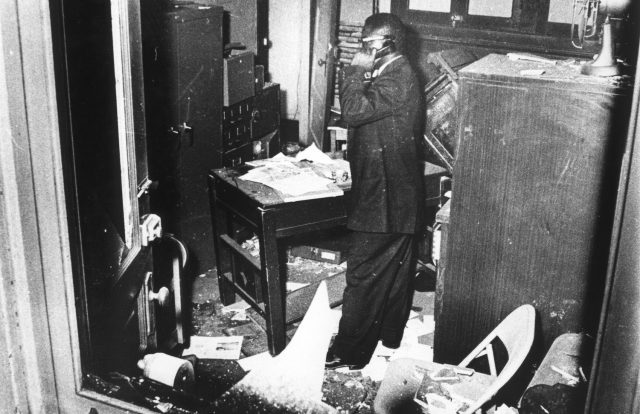

Inside, the rear section of church was in shambles. The force of the blast twisted chairs, shredded wooden benches, and knocked out windows. Even a block away, windows were blown out of buildings, and occupants of houses said they were jolted off their feet. Police at City Hall, three blocks away, at the time said the building seemed to shudder.

McCaw recalled the devastating incident: “We were all in Sunday school classrooms when the bomb went off. I told the children in my class to lie on the floor. The teachers kept the congregation from panicking. We couldn’t get to the children in the basement. Everyone walked outside in a hurry. There was no screaming, only crying,” she told The Birmingham News on Sept. 15, 1963.

Cars in the general area were overturned and dented with rocks. Three that were parked near the church side entrance were knocked four feet backward by the explosion; sides of the almost-demolished vehicles were dotted with large holes, caused by flying debris. The church and nearby buildings were in shambles. The basement wall on the 16th Street side of the church was torn open, leaving a gaping hole. Just inside, the women’s lounge was demolished.

Across 10th Street, the buildings in the Black district were now windowless. Among the businesses damaged in the area were Social Cleaners, Jockey Boy Restaurant, Liberty Contracting Company, and Silver Sands Restaurant.

At the time of the explosion, the Rev. John Cross, then-pastor of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, remembered being in the women’s Bible study class, which met on the 16th Street side of the building.

“It was a wonderful lesson too, ‘a love that forgives’. People seem to have love, but they don’t know how to forgive,” he told historian Horace Huntley in 1997 for the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute’s Oral History Project.

“We’d been having difficulty with our hot water heater in the kitchen area, and I thought it was the tank that had exploded down there. Then, in a few seconds, I didn’t smell gas fumes, I smelled powder fumes. Immediately, I recognized that the hot-water heater didn’t blow up, it was a bomb or something that went off.

“There were some people that were injured, and they were being taken to the hospital…. I went around to look at the hole in the east side of the church. All I had to do was just bend over slightly and could walk right in…. We saw this bunch of debris there and they started digging down in there and less than two feet down we saw a body. We took that one out. They brought a stretcher in and dug down a little bit more and saw another one. So, they were all on top of each other, as if they had hugged each other.”

When The Bomb Went Off

Ambulances moved in, then out with the injured and dead. Killed in the blast were Wesley, Robertson, Collins, and McNair. Besides killing the four girls, the explosion left nearly two dozen injured.

Also killed that day was 14-year-old Virgil Ware had died that day at the hands of two young white men, Michael Lee Farley and Larry Joe Sims. Ware was killed on his way back from Docena, a community just outside Birmingham, where he and his brother James had gone to buy a bicycle for Virgil’s paper route.

After the bodies of the girls were taken from the scene, Cross said officials heard what appeared to be moaning in the toilet stalls in the bomb-ravaged lounge. There they found 12-year-old Sarah Jean Collins, sister of Addie Mae.

“I didn’t recognize who she was at the time, blood was streaming down her cheeks, and she did seem incoherent,” Cross said.

Sarah suffered extensive damage to her left eye and spent more than eight weeks in the hospital. Sarah, the youngest of the eight children of Arthur and Alice Collins, was very close to her sister, Addie Mae.

On the day of the church bombing, Collins-Rudolph remembered it being a good morning when she and her sisters walked to church from their Smithfield home. “It was Youth Day, and we were going to take up the offering. [The kids] were going to do all the things the adults usually do,” Collins-Rudolph told the Birmingham Times in a previous interview.

Collins-Rudolph and her sisters had been in Sunday school before entering the restroom.

“When Sunday school ended, [Addie Mae and I] were still in the ladies’ lounge, but [our older sister], Junie, had gone to her class,” Collins-Rudolph said. “I was waiting for class to [end], and I saw [Carole, Denise, and Cynthia] come in. We stayed in with them. They went and used the restrooms, while Addie and I were standing in the lounge. She was standing right by the couch, and the couch was right where they had placed the bomb. When [the girls] came out of the restroom, they all came out together and went over to Addie. That’s when Denise asked Addie to tie the sash on her dress. I was standing by the sink, and we all stood there waiting to see her tie it.

“That’s when the bomb went off. Boom! By the time [Addie] reached her hand out to tie [Denise’s sash], the bomb went off. The debris came from the [shattered] glass window and blinded me. All I could do was say ‘Jesus!’ because it scared me so bad. Then I called out, ‘Addie! Addie!’ The first thing I thought was that they ran back into the Sunday school area. I didn’t have any idea that they all had perished.”

Collins-Rudolph said one of the church’s deacons rescued her.

“I heard somebody holler, ‘Somebody bombed the Sixteenth Street Church,’” she recalled. “I was told that a deacon, Samuel Rutledge, jumped down because the bomb had blown the steps away. He jumped down, looked in there, saw me bleeding, came in and got me, and took me out the hole that the bomb blew. When he took me outside, the ambulance was already waiting. He put me in the ambulance.”

She remained in the hospital until early November while doctors treated her eye injuries. She had to return to the hospital the next summer to have her right eye removed because it had become infected, and the infection threatened to spread to her left eye.

Collins-Rudolph said she cannot put the bombing too far from her mind.

“It’s something that’s sad,” she told the Birmingham Post-Herald in 1988. “You go to church with your sister … and the next minute you know you won’t see your sister again because of somebody doing something terrible like that. I try not to think of it because it always hurts,” she said. But she added, “I will never get over that feeling.”

When the blast went off, Claude Wesley, 54, a principal at Lewis Elementary School, was having his car tank filled with gas. He abandoned the car and ran to the church but didn’t find his daughter Cynthia. He went to University Hospital, where he was asked if the girl was wearing a ring. “I said, ‘Yes,'” Wesley recalled. “They pulled her little hand out, and the little ring was there,” he told the Birmingham Post-Herald in December, 1963.

With the theme of “Looking 60 years forging Justice for a Better World,” the historic Sixteenth Street Baptist Church will commemorate the 60th year anniversary of the church bombing on Friday, Sept. 15 at 9:30 a.m. The morning will feature a special keynote by the first African American female U.S. Supreme Court Associate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson. For more information, go to www.16thstreetbaptist.org.