By Michael Sznajderman

Alabama Newscenter

As Birmingham residents pause to reflect during this 150th year since the city’s founding, there’s been no halt to the evolution of two historic downtown neighborhoods.

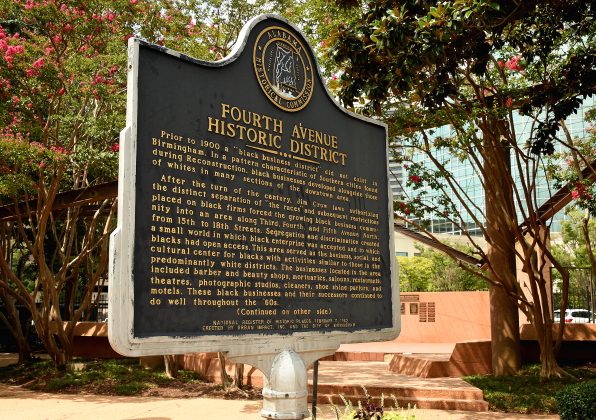

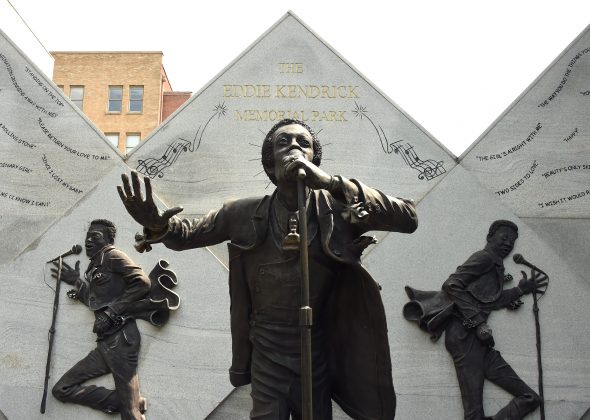

In the Fourth Avenue Business District, the historic center of Black entrepreneurship and culture in the city, projects large and small promise to transform the neighborhood and create new vibrancy.

A few blocks away, in the Civil Rights District – which four years ago achieved federal designation as the Birmingham National Civil Rights Monument – the restoration of a historic motel and other projects is expected to draw more tourists, businesses and entrepreneurs to the west side of downtown.

“This is a great time, not only to be in the Fourth Avenue District and the Civil Rights District but in Birmingham as a whole,” said Ivan Holloway, executive director of Urban Impact, a nonprofit community and economic development agency fostering growth in both districts.

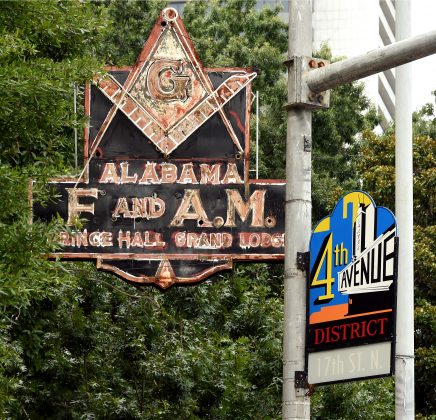

Holloway has reason to be excited. At the center of the Fourth Avenue District, at 17th Street, the curtain has been raised on a multimillion-dollar re-envisioning of the historic Carver Theatre and Alabama Jazz Hall of Fame. Across the street, plans are firming up for a dramatic transformation of the long-shuttered Masonic Temple.

Just to the north, in the Civil Rights District, restoration of the A.G. Gaston Motel is underway. Built by the late Black entrepreneur and millionaire A.G. Gaston, the motel is where, in 1963, national civil rights leaders including Martin Luther King Jr., Ralph Abernathy and Fred Shuttlesworth gathered for strategy sessions during the campaign to dismantle segregation in the city.

A few blocks from the motel and the adjacent Birmingham Civil Rights Institute, the Ballard House has undergone renovations. A nonprofit offers programming and exhibits about the Black community that thrived west of downtown through much of the 20th century.

And up the block from the Gaston Motel, a new space has opened in the Arthur Shores Building, with the promise of bringing entrepreneurs and small businesses to the district.

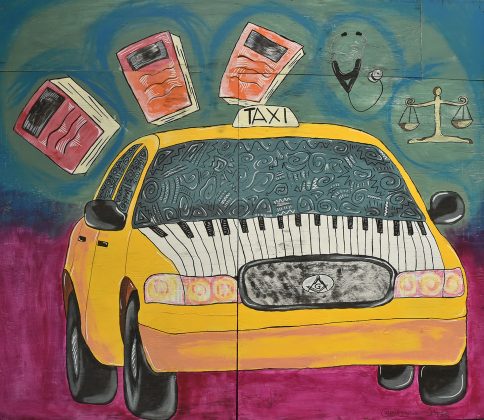

“Birmingham is a true gem – a hidden gem – and this building was, too,” said Danielle Hines, owner of the Shores Building, which was a postal warehouse in the 1920s. In June, Hines held the grand opening for CREED 63, an entrepreneurial coworking venture occupying a portion of the structure. The building also houses law offices and retail space.

Hines purchased the building from the family of Shores, the pioneering Black attorney who represented King and others during the civil rights era. One of Shores’ daughters, the late Helen Shores Lee, also became a lawyer and Hines – a lawyer, too – clerked for Lee when she was a Jefferson County circuit judge.

“When she offered me the opportunity to purchase this building, it was a no-brainer,” Hines said.

After securing the building in late 2018, Hines worked with community leaders to study the building and determine its best use. The idea of creating a coworking space emerged from that process.

In addition to providing a place for entrepreneurs to interact and grow, CREED 63 plans a variety of programming, open to all, hosted by nonprofit organizations such as Urban Impact and REV Birmingham focused on neighborhood revitalization and business development.

“The space is a community space – that’s what it’s here for,” said Hines, who noted that demand is outpacing capacity. “It’s been really exciting to see folks wanting to be here, wanting to be in this space, curious about what we have to offer, curious about how they can participate and be a part of what we’re doing here.”

Urban Impact leader Holloway said it’s inspiring to see all the activity in the Fourth Avenue Business District and the Civil Rights District, both of which are part of the larger Fountain Heights neighborhood that stretches south to Morris Avenue, and north beyond Interstate Highways 59/20, the Birmingham-Jefferson Convention Complex and Oak Hill Cemetery, where some of the city’s founders are buried.

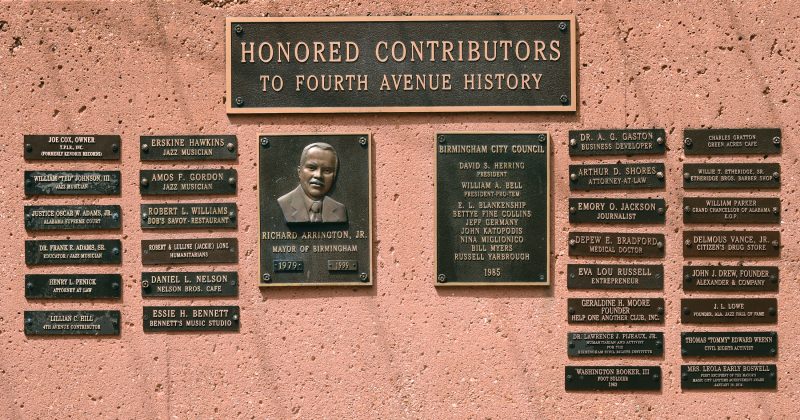

It’s an area “with a rich history of African American culture and entrepreneurship,” said Holloway. He noted the Fourth Avenue district was where local Black leaders, including the pastor of Sixteenth Street Baptist Church, pooled resources in the late 19th century to create the Penny Savings Bank of Alabama, the first Black-owned financial institution in the state and one of only three in the nation at the time. By the early 1910s, it had grown to be the most secure Black-owned bank in the country, financing many Black homes and businesses before it failed following a merger. The bank’s six-story headquarters, built in 1913, still stands on 18th Street North.

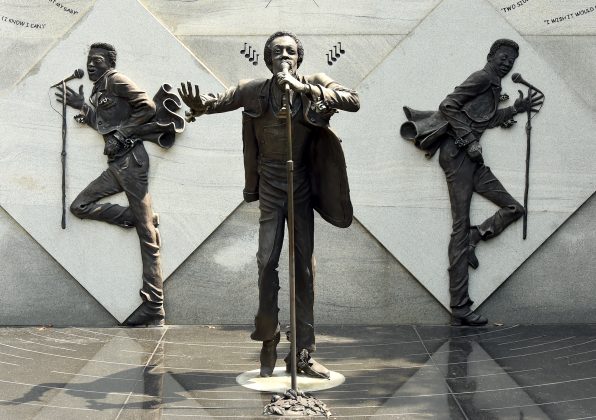

The Fourth Avenue District only grew in vibrancy during the Jim Crow era of segregation as Black businesses, restaurants and taverns, entertainment venues and professional offices concentrated in the neighborhood.

“The Fourth Ave Business District played an enormous part in making sure people had access to the necessities of life at that time,” Holloway said. “It was a community within the downtown construct of Birmingham.”

Nearly 60 years after desegregation opened doors for Black businesses to spread to other locations, as much as 35% of the properties and businesses in the Fourth Avenue District are Black-owned. That compares to an estimated 7% nationwide.

Holloway said Urban Impact continues to work to increase economic opportunities for Blacks and Black-owned businesses. “African Americans are part of the Birmingham economy in a very meaningful way. They not only add value, but add context to the Birmingham story,” he said.

Urban Impact is working to incorporate the Fourth Avenue district history into the broader story of civil rights being told a few blocks away.

“We know that the Civil Rights District has visitors from all over the world,” Holloway said. “We see this as a great opportunity to transform the Fourth Avenue district in a historical manner that gives context and further develops the story line of the work of African Americans.

“If we can recreate … some of that, it not only provides a service, but it tells a story about our ability to make it in this society, no matter what hindrances were put forth,” Holloway said.

Urban Impact and other downtown organizations are working on a broader plan to bring together the Fourth Avenue and Civil Rights districts and other downtown areas and neighborhoods. They include to the west, “The Switch,” the name for the city’s innovation district, and Titusville; the Parkside area to the south; the residential areas of Fountain Heights to the north; and the central business and government centers to the east.

“There is an enormous amount of history, talent and opportunity located in our neighborhood that need to be connected to what we are doing in downtown Birmingham,” Holloway said. “Our goal is to really sew as much of the fabric of our surrounding communities back to downtown.

“We see this as a great opportunity to tell a wonderful story about Birmingham,” he said. “We want people to come here and leave excited, more knowledgeable, and filled with pride and energy.”

The story appeared originally on the Alabama Newscenter website.