By Cynthia Silva

CNN

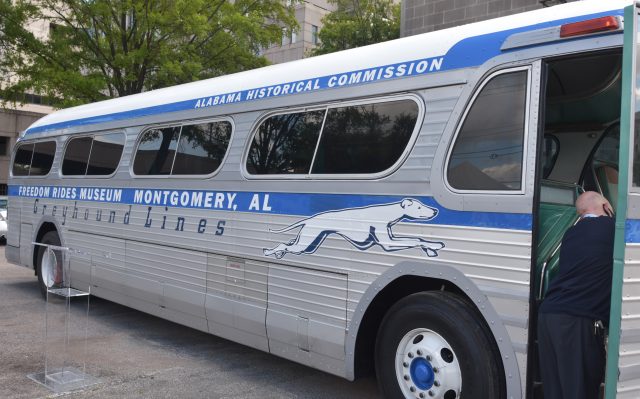

A restored vintage Greyhound bus was unveiled last month to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the Freedom Rides.

The bus, which was in service during the Freedom Rides — a series of political protests against racial segregation in 1961 — was unveiled at the Alabama Historical Commission’s Freedom Rides Museum in downtown Montgomery. The May 4 date of the unveiling coincides with the day the first Freedom Riders left Washington, D.C., bound for New Orleans to protest segregated interstate transportation terminals.

“As we celebrate the arrival of the restored Greyhound Bus and its symbolic representation of the courage of the Freedom Riders, we also commemorate the 60th anniversary of the rides and their impact on equal rights for all Americans,” Alabama Historical Commission Chairman Eddie Griffith said in a press release.

The restored vintage Greyhound bus includes a soundscape exhibit, which plays music and firsthand accounts, and rolled into Birmingham last month.

The Freedom Riders, who included Black and white civil rights activists, participated in the bus trips throughout the Jim Crow South. Organized by the Congress of Racial Equality, the purpose of the rides was to pressure the U.S. government to enforce the 1960 Supreme Court ruling in Boynton v. Virginia, which made it unconstitutional to segregate interstate transportation facilities, including bus terminals.

Thirteen riders, including John Lewis, the civil rights leader who went on to become a congressman from Georgia, left the nation’s capital May 4 to reach New Orleans. However white mobs attacked the riders at bus stations.

The violence grabbed the attention of then-U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy, who negotiated with Alabama’s then-Gov. John Patterson, to secure protection for the riders. However, as the riders departed Montgomery for Jackson, Mississippi, on the morning of May 20, a white mob attacked them with clubs and baseball bats. Police were nowhere in sight.

The rides continued over several months and, as the violence received national attention and hundreds of riders joined the movement, increased pressure from the administration of President John F. Kennedy led to the Interstate Commerce Commission officially prohibiting segregation in interstate transportation terminals.

The restored bus will become a permanent exhibit of the museum.

“History happened here,” said Lisa D. Jones, executive director of the historical commission and the state historic preservation officer. “Preserving this place helps bring to life a critical part of the civil rights story, and the role Montgomery and the state of Alabama played in it.”

In May, two Birmingham natives who participated 60 years ago in the historic Freedom Rides told their stories to an inquisitive and admiring crowd at the Birmingham Public Library.

Catherine Burks-Brooks and the Rev. Clyde L. Carter weren’t on the first two buses that left Washington, D.C., on May 4, 1961, that were attacked by pro-segregation mobs in Anniston and Birmingham. Rather, they were part of the subsequent wave of young blacks and whites who continued the rides on interstate buses later that month and through the summer of 1961 with the goal of permanently crushing segregated public transportation in the South.

“That we were making history really never crossed my mind,” said Carter, 90, former pastor of Westminster Presbyterian Church in the Titusville neighborhood of Birmingham. Carter was attending Johnson C. Smith College in Charlotte, North Carolina, following service in the Navy, when the attack on the first buses took place in Alabama.

A classmate convinced Carter they needed to get involved, and the two joined a bus in Charlotte that traveled to Atlanta and then to Montgomery, where they were arrested, along with civil rights pioneer Ralph Abernathy, for attempting to integrate the bus station’s lunch counter.