By Erica Wright

The Birmingham Times

A tour of the Vulcan Park and Museum (VPM) captures the history of the Magic City. It begins with a wall of iron products—skillets, pots, pans, knives, forks, shovels, furnaces—that tell the story of Birmingham’s booming steel and iron industry.

The wall is used as “a teaching tool to introduce students to the concept of iron and why it’s important. It describes what things were made from iron, how they are still used in their lives, and how industry built this city,” said Jennifer Watts, VPM Director of Museum Programs. “This city was planned around the mineral resources that early surveyors found here.”

Join the Birmingham Times for a tour of the museum’s galleries, all of which are connected and conveniently located on one floor.

Interactive Experience

Following the wall of iron products, is a gallery that features the three ingredients that make up iron: iron ore, limestone, and coal—all of which were found in Birmingham. This gallery also includes a timeline that illustrates the founding of the city and the iron industry boom. It tells stories of workers and factories through the eyes of four different men who had experience working in the early days of the Birmingham iron industry.

“We see immigrants moving here because they want better lives for their families,” said LaShana Sorrell, VPM Director of Public Relations and Marketing. “You still see that in Birmingham today through the large Greek, Jewish, and Italian communities that still reside in the city. [They are the descendants of] immigrants who came here to work in iron ore and mining.”

Old-Time Country Store

Next is a gallery set up to look like an old country store. It showcases a wall with shelves of canned goods and other products, such as linens, as well as a countertop with an old cash register and a glass display of pots, pans, and other products made from iron.

“Iron factories had what was called a company store,” said Sorrell. “This store was similar to what’s happening now with [the city’s] revitalization—condos being built where people work, live, and play. It was kind of like you work here, stay here, and shop here. Instead of paying with cash, employees would use ‘clacker,’ [scrip, or a substitute for government-issued money, issued by a company to pay its employees], … for their transactions. They could get what they needed [at the company store]: food, fabric, and many [other] things.”

The gallery also features photos of company-sponsored events, including picnics, dances, and performances.

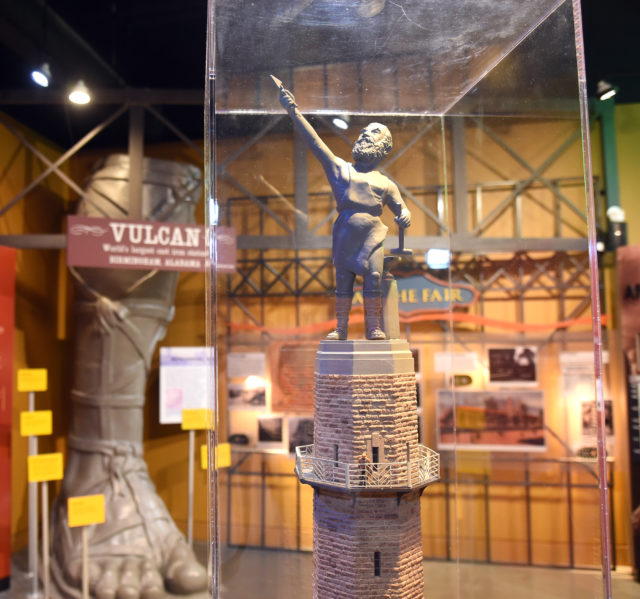

The Vulcan Room

Next on our tour is the Vulcan Room, which tells the story of how Vulcan came to be. In the middle of the room sits a glass-enclosed miniature replica of Vulcan on his pedestal, as well as a statue of Vulcan’s foot and the story of Giuseppe Moretti, the Italian-born sculptor who was commissioned to design Vulcan.

“The [Commercial Club of Birmingham] in 1903 decided that Birmingham needed to send something to the [upcoming] World’s Fair in [St. Louis], and they [chose] to build the largest cast-iron statue. … They went around asking artists if they could make a colossal statue out of iron in time for the world fair in 1904, and they all said, ‘No.’ Then they talked to Giuseppe Moretti,” said Watts.

Moretti, an Italian immigrant who was a sculptor by trade, took on the challenge and pulled it off.

“He started building the clay model in a church in New Jersey. It was cut up, molds were made, and the pieces were [sent to Birmingham] to be cast in iron. It was a multistep process,” Watts explained. “[The statue] was cast at what is now Sloss Furnaces, almost bankrupting the company in the process. All local materials were used, and a bunch of local guys were hired … to cast it. Vulcan was made in 26 pieces. As each piece was made, it was shipped one by one by rail to St. Louis for the fair.”

At the 1904 World’s Fair, Vulcan won several awards and fascinated many people, making people realize that Birmingham was a good place to move.

“It spawned much of that growth around that time period and contributed to that boom,” said Watts. “That’s where Birmingham gets its nickname the ‘Magic City,’ because it grew overnight as if by magic.”

Vulcan stayed in St. Louis for about a year. When he was returned to Birmingham in 1905, he was left on the side of the railroad tracks for a long time due to a bill not being paid. Eventually, Vulcan was put up at the Alabama State Fairgrounds.

The Great Depression

After leaving the Vulcan Room, we enter a gallery with a timeline display of the Great Depression, World War II and women in the workforce, and how the iron industry ties into those moments. Next up is a section on the Civil Rights era.

“We encourage people to visit the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute for a complete story,” Watts said. “What we give here is a summary of what happened via a video and print history about [Birmingham Civil Rights icon] the Rev. Fred Shuttlesworth, showing him walking with the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. We [provide an overview of] what happened in Birmingham at that time.”

Exhibits

From the Civil Rights area, the tour goes into the Linn Henley Gallery, where special exhibits are housed. Currently on display is “Terminal Station: Birmingham’s Great Temple of Travel,” which will run through December 31. Other exhibits have included “Alabama Justice,” based on the Alabama bicentennial celebration that spotlighted landmark cases in Alabama that changed the landscape of the nation; an art exhibit about Ramsay High School; and exhibits about different communities in Birmingham, including the Italian and Greek communities and the Historic 4th Avenue District.

“Terminal Station: Birmingham’s Great Temple of Travel” highlights the historic downtown Birmingham Terminal Station train depot, which was demolished 50 years ago. In the center of the room is a replica of the once-bustling passenger rail station, along with plaques surrounding the replica with information about the former city landmark. Above the replica hangs some drawings and pictures of the train depot’s design, which featured a 100-foot-high dome and twin towers. Along the walls are pictures and more details about Terminal Station, as well as memorabilia such as signs and clocks.

“It recalls the history of the station, describes the beautiful architecture, and tells of the travesty of it being demolished,” Sorrell said. “One thing that demolition gave [Birmingham] was a sense of urgency that we need to put historic preservation at the forefront, which is what spearheaded all of the preserving we’ve been doing since then over the last 50 years.”

The upcoming exhibit will be “Rider Privilege: Alabama Women and the Vote,” which commemorates the passage of the 19th amendment in 1920; it will run from January to December 2020.

Our tour ends with a visit to the gift shop in the museum lobby, but you can continue enjoying your visit to VPM by taking a walk along the mile-long Vulcan Trail, which scales the ridge of Red Mountain. The route runs below the 10-acre Vulcan Park, where you can take in the views of the city or visit the top of Vulcan.

Vulcan Park and Museum is open every day from 10 am to 6 p.m. For more information, visit www.visitvulcan.com.