Lunching With El Jefe in Havana

Ericka Blount Danois

©2016, The Shadow League

Just a few months prior to my first trip to Cuba, my second child, Laila Assata Danois, was born on August 13, 2002–Fidel Castro’s birthday. I had been working from home and nursing her, but had started back working periodically.

In the office where I worked as a staff writer at an alt-weekly, I read the black newspaper, The Afro American on a weekly basis. One day I saw a story on the front page with a picture of Fidel Castro and a picture of the National Black Farmers Association, a group that was looking for overseas opportunities to sell their produce after being discriminated against by the USDA in garnering loans.

John Boyd, the president of the National Black Farmers Association recalled at one point that a loan officer threw his application in the trash can as he sat across the desk from him. Boyd, a fourth-generation farmer, still tilled the soil that was passed down from slavery, from slaveholders who thought the hilly land they gave his family after emancipation was useless.

To me, this story was huge. And no other mainstream outlet was covering it. The farmer’s association had just begun talks with the Cuban government about selling their produce to them, and were taking a second trip in hopes of finalizing an agreement that would help them gain independence from the federal government.

Black farmers, after being duped by the 40 acres and a mule promise, were facing extinction at only 1 percent of the farming population. This deal would mean a steady market for them. White farmers from the Kansas Farm Bureau had brokered a $200 million dollar deal with Cuba the year prior.

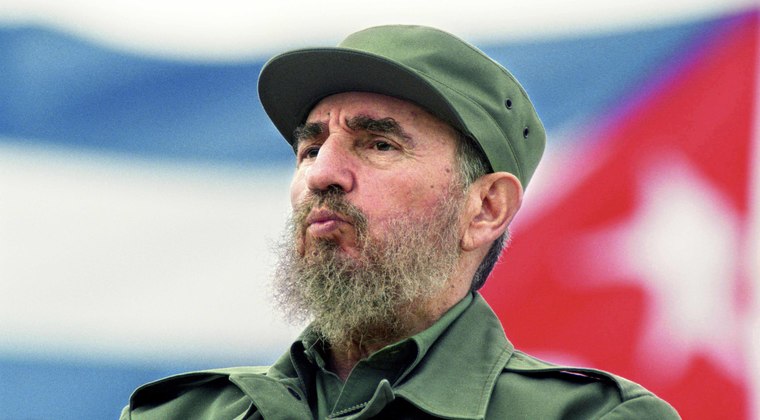

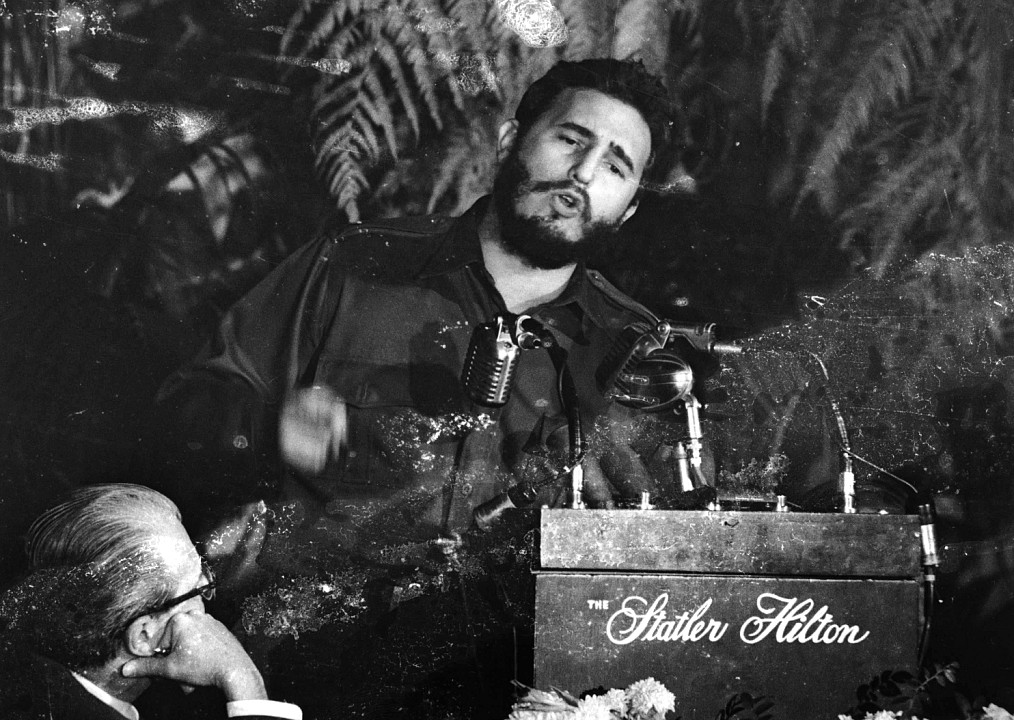

Fidel Castro and Cuba were constant topics in my household growing up, and as an adult. My sister had been to Cuba and talked with Assata Shakur. As kids, we learned from our parents about him meeting Malcolm X at the Hotel Theresa in Harlem.

I watched the Sun City music video and later learned about Cuba sending 25,000 troops in the struggle to dismantle apartheid in South Africa, while the U.S. was still diplomatically supporting it. He inspired and formed alliances with the independent movements of Nelson Mandela, Kwame Nkrumah, Hugo Chavez and Julius Nyerere, among others. He harbored political prisoners and Africans and African Americans in exile, including Assata Shakur and Nehanda Obiodun.

As an adult, I learned that their medical school was one of the best in the world and they offered full tuition to scholars of color, including black Americans.

I was going to get to Cuba and cover this story, by any means necessary.

I called up Boyd and told him that I wanted to cover the story for my newspaper. He was all for it. I spoke with my editor, who was interested in the story, but unwilling to pay for me and a photographer to go.

I wasn’t deterred.

I ended up footing the bill (later getting reimbursed by the newspaper). My mother, who owned a photography business and worked as a photographer, would go as my freelance photographer. We were off to Miami and then to Cuba.

We stayed at the Hotel Habana and traveled throughout Cuba for the first two days, visiting farms in Santiago de Cuba, Havana and other areas around the countryside. In the evenings we were hosted by representatives of the Cuban food import company and ate at restaurants with salsa music and dancing.

We met people who were happy to see black people from the States. People who when we mentioned Baltimore, asked about the Orioles, remembering the exhibition game they played against the Cuban national team in 1999. We visited Callejon De Hamel and met the artist Salvador Gonzalez Escalona who made the streets so beautiful with his murals.

On the night prior to the day we were set to head back to the States, we got a call in the hotel room my mother and I shared. It was midnight and I was sleepy after having dragged heavy camera equipment around with us most of the day. On the other end of the line was John Boyd. His voice was low, alternately hushed and managing excitement.

“The president wants to have lunch with us tomorrow,” he told me.

“What president?” I ask. I’m thinking, the president of the food company? The PTA president?

“Fidel Castro,” he says.

“Oh, ok,” I said, trying to sound normal and mature. I asked him what time we were meeting and where and then I hung up the phone, turned to my mother and screamed.

The next day, we met the delegation and boarded a bus to an undisclosed location. None of us knew what to expect. Would there be an army of police officials with rifles surrounding him? Would he be like Prince, where he didn’t allow you to record or take notes during interviews?

Would I mess this up? Is this really happening? How did I get here?

We reach an anonymous building and pass security checkpoints. We are all nervously silent.

As the elevators open, El Comandante is waiting there. There are no bodyguards, no cameramen, no dogs, no police with rifles–not even the makings of an entourage. Just President Fidel Castro smiling in his standard attire of army fatigues and black sneakers.

He greets everyone warmly and he sits down at the lunch table. I sit next to his interpreter and he sits next to her. I am afraid to try my college-level Spanish now. Ordinary Cubans have been complimenting me on it, but I’m not so sure about their encouragement now. I try it anyway, telling him about my daughter who was born on his birthday.

He tells me that I must bring her on my next visit. After talking with him for a while and butchering verb conjugation, I resort back to English through his translator.

He fingers a rum-laden mojito–the national drink of Cuba. Castro has given up smoking cigars, he says through his translator, after the Cuban government began its campaign against smoking. “But then, everyone has the right to commit suicide,” he adds with a laugh and a mischievous twinkle in his eye.

El Comandante’s black digital watch reads 1:04. But no one is pressed for time.

Right before this lunch, the group of farmer’s have signed an agreement for a $25 million dollar food contract.

Fidel touches Boyd on the hand and says, “I see that it has not been a useless trip. You have made progress, and I am glad to hear that.”

Castro listens intently as everyone introduces themselves. He talks with each person before announcing that he is very hungry and is ready for his guests to eat lunch with him. “It would have hurt me if you had left and I had not had the chance to meet you,” he says.

As everyone sits down at a table in the parlor, Castro asks what careers blacks in the Southern states pursue.

“Those that can afford it go to college,” Boyd begins.

“Exactly, that is a major issue,” Castro says.

“A lot of them look at technical careers,” Boyd says.

“Even in our country where we have 90 percent literacy and semi-literacy, with the passage of time, we realize it is not enough to simply give everyone the same opportunity, because some people come from so far behind,” he says, touching his hand to his forehead and pointing his finger to make his point. “It comes from social status. Children with parents that are professors will continue to make it to the elite schools. Now we have programs to try to alleviate this.”

Castro talks about the importance and the status of HBCUs in the States and he and Boyd talk about the financial struggles of the colleges.

“I am very glad of the results of this visit,” Castro says, dipping into his large plate of French fries. “We have many visitors here–sometimes it is not easy to meet everyone, but we have our priorities. I remember the fine meeting we had before, so I am very happy that you have your letter of intent. The young man that talks about my visit to Harlem, there is that sentiment that brings us together,” says Castro, alluding to Cuba’s active kinship with marginalized communities around the globe. “It is more than trade, it is friendship.”

“We can help introduce you to Third World markets,” he continues. “There are people who need to buy lots of food in the Caribbean and Africa.”

“We would appreciate advice or help with that,” Boyd says. “We would be happy to know these countries.”

It is 3:30 by the time everyone is finished with lunch. Before we leave Castro gives the women bouquets of flowers and hugs and all of us a box of Cuban cigars. We pass through customs without any problems.

We were all silent as we got on the bus to the airport, trying to process what had happened. Lydia English, the translator for The Black Farmer’s Association, finally broke the silence. “I can’t believe that just happened,” she said. “It’s all so surreal.”

My mother and I joked about how Castro had a way with women and how tall and down-to-earth he seemed to be. He had asked my mother about how many children and grandchildren she had and he told her he had five sons and five daughters. (He reportedly has many more).

We had just witnessed history up close. We figured no one was going to believe us. We could barely believe it ourselves. Fortunately we had proof with the pictures. We were nervous about going through Cuban customs, but they let us through with a smile, Cuban cigars in tow. Like Lucy and Ethel, we had done it again.

To paraphrase the eloquent urban poet and philosopher Ice Cube, “It was a good day.”

This story originally appeared on TheShadowLeague.com, a site dedicated to journalistically sound sports coverage with a cultural perspective that insightfully informs sports fans worldwide.